Dear Gentle Readers,

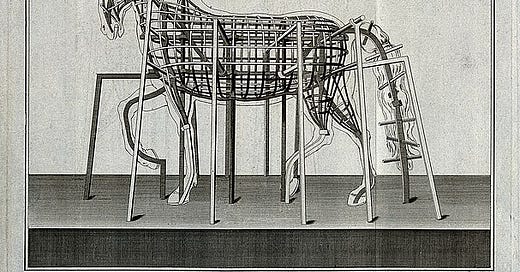

Ha-ha, I am beginning to see—to feel, to hear, rather—a bit of a rhythm to this process of writing about recent bits of writing on a work in progress. On Sunday or Monday I sit down and think through what I’ve written during the past week. I can also look through what I wrote months and months ago and see what’s ready for a rewrite in light of a newly firmed-up frame and structure—an armature—for the novel.

I look for problems that are a little sticky, that offer material to work with, improvement I might find in the process of thinking about it—but, importantly (I think), which I’m not directly working on exactly in this moment. My thought is that those bits that are truly in progress should stay a bit longer between me and my mind when I’m walking or maybe sleeping or in whatever mysterious mental states result in figuring things out and giant, bright leaps forward after what seems like endless dull fields of nothing and no advances.

This week I was reading The Anomaly, a novel by a very popular French author I had never read before, Hervé Tellier (here’s a fascinating interview with Tellier, who was a late member (meaning he joined late, not that he’s dead!) of the Oulipo constraint-based literary movement and is now its president). It’s fast-paced, exciting, and very impressive, and I’m enjoying it a lot. It doesn't feel especially Oulipan so far, although this review discusses the constraints Tellier uses, which I hadn’t really noticed. Each chapter offers a little story of sorts—many of them very sad or poignant, all with the feeling of being perfect snapshots of how life really is, in very distinctly drawn characters, not stereotypes or generics. There is a developing mystery that holds my attention easily. I wondered at Tellier’s skill in describing a pilot at his work, handling technical details with ease that made it convincing and easy to read. Then he did it again with a range of other professions and people of different ages and backgrounds. All equally, terrifically realistic and smooth.

I noticed that this style—very clean, unaffected, third person and objective-feeling, particularly good at gracefully, effortlessly describing things you’d need tremendous research to know—reminds me of other writers. In particular, of Maylis de Kerangal, whose Mend the Living I described and quoted from in this previous Live More Lives. I read her in English translation from the original French, too. And then I thought, too, of Jenny Erpenbeck, whose The End of Days (originally in German) made me burst into full-on tears during the long daylight flight home from London. And yet it has left very little trace. Like the others, the feeling of these effective, moving, accomplished and very beautiful novels is one of becoming party to the great wonder and tragedy of existence—but from behind a lens, with the affective power of the story being so strong that it gets you, and yet because of the perfectly frictionless style, it does so without ever really leaving its grooves in your mind. As if a terribly tragic or disturbing story you read in the newspaper haunted you for days or years after (has this happened to you? It has happened to me, more than once.).

This is, actually, precisely what the great pioneer and theorist of the realist novel, Gustave Flaubert, wanted—even as he idolized ‘style’ and considered it far more important than ‘subject’ or ‘story’—he also sought to write a novel that observed the world as impersonally as God. The very excellent critic James Wood quotes Flaubert asking a friend:

When will all the farts be written from the point of view of a superior force, that's to say, as the good God sees them, from on high?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Live More Lives to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.