Dear Gentle Readers,

this week I know I need to take a little time off to catch up on the excessive number of articles on an excessive number of subjects that I’m working on right now, as well as the novel that I talked about so lovingly, so tremulously, on Friday. But over the past weeks of books taken out of the library and fewer books returned to the library, of second-hand books of random and various interest not resisted when spotted in the Little Free Libraries that dot my neighbourhood and that I browse like an idle shopper on every daily walk, of many books started and some books finished, I have gathered quite a lot of pages with their corners scandalously turned down (I’m a very bad person) to remind me to go back and share a passage with you.

Let me look at the carefully and multiply-piled (to create a semblance of order that fools no one) little skyscrapers made of books on the floor to the left of my beautiful but way-too-small-for-a-spreader desk, and see what I can find for you.

In Tom McLeish’s interesting non-fiction book, The Poetry and Music of Science: Comparing Creativity in Science and Art, McLeish, a professor of natural philosophy and an Anglican believer in the tradition of the religiously-motivated scientists of the later 17th century in England, cites another writer, Pat Waugh, for the insight that “the novel is the experimental medium of artistic creation para excellence.” He goes on:

In the safe space of the novel, inhabited worlds can be summoned into existence and their dangers and dark places explored. Questions of the relationship of human beings to time and space, to each other and to the Earth can be teased out in both internal and external worlds of their characters. The novelist does not experience unconstrained freedom, however, but discovers the multiple moral constraints of the experimental form. Crucially, novelistic writing forces a more intense outward gaze.

‘Outward’, in this sense of escape from or forced abandonment of solipsism, can include inward, examining the motivations and details of our inner as well as outer worlds, much like the physicist or biologist who can take equal delight in the movement of galaxies or the movement of atoms, in the great desert or tropical biomes or in the microbiome that inhabits our gut or nasal passages.

I got stuck about a third of the way through Vladimir Nabokov’s The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, which I have heard is a wonderful, wonderful book, and yet which by this point still hadn’t really grabbed me. I will try to keep trying and hope some spark of interest catches fire, as I’ve been promised it will. But no worries, I still managed to desecrate the book with a friendly turned-down corner to remind me of this passage—from the character Sebastian’s supposed work—that rang so true to my own sometimes perverse way of thinking:

But because the theme [in this case, it’s the theme of the ‘banished man pining after the land of his birth’, but that’s not what caught my attention] has already been treated by my betters and also because I have an innate distrust of what I feel easy to express, no sentimental wanderer will ever be allowed to land on the rock of my unfriendly prose.

That point about distrusting anything that seems too easy to say is something that I think is sometimes a strength in my thinking, and sometimes a definite weakness. I’ve had to learn (through reading, of course, as well as through living) that sometimes the straightforward, rather than subtle, expression of an ordinary emotion or idea is the most poignant and natural and real.

I’ve been reading a very nice novel called The Cat and the City, in which the author, Nick Bradley, draws terrific portraits of a very diverse group of disparate characters living very different lives in Tokyo. The following two paragraphs go quickly from pain to beauty as part of our immersion in the experience of Ohashi, a withdrawn, unhoused, meticulous and proud former rakugo performer (a storyteller). Although we start here with a particularly terrible moment, the reader first encounters Ohashi in the novel in a way that establishes our respect and sympathy right away. But as well as contrast, this passage had the bonus virtue of elegantly employing the little-used collective noun for cats: a group of cats is a clowder:

Either way, the pain lessened as the beating went on. It was better to relax the body and not resist, then there would be fewer broken bones. The worst was if they kicked a tooth out. That made eating harder. Ohashi did his best to protect his head from the attacks. But then a foot or a fist or an elbow would catch him in the testicles. And then that was a whole new pain that ate away at his stomach from the insides.

Whenever Ohashi went out collecting cans, he tried his best to look around the streets and take in his surroundings. To view the things in the scenery that he felt to be beautiful, the small things that gave him pleasure. The sun rising in the morning, edging its way through the gaps between the buildings, the hazy sky that obscured the tops of the skyscrapers in the distance, the clouds that formed patterns that looked like a clowder of cats chasing one another. Life still had some pleasure for him, no matter how small.

And, penultimately, a passage from the many, many folded page corners of Mircea Cărtărescu’s Solenoid, which I’m reading very slowly (just whenever I take the subway around forty minutes each way to visit my parents, where it makes the time go very quickly). This is a set of questions posed by Virgil, a Picketist (in the novel, Picketism is a sort of cultish movement in protest of horrible existential realities that gets its name from its adherents’ habit of picketing morgues and cemeteries in protest against death):

Where does happiness come from? How is the infinite misery of our lives possible? Why do we feel pain, why do we suffer illness, why have we been given the pains of jealousy and unrequited love? Why are we wounded by the people around us? Who approved cancer, who released schizophrenia into the world? Why do amputations exists, who allowed torture machines to come into our minds? Why do people extract teeth to extract confessions? Why are bones crushed in traffic accidents? Why do airplanes crash, why do hundreds of people fall, for long minutes, knowing with absolute certainty that they will burn, they will explode, they will be torn apart and crushed? Why do people die of hunger, why are they buried under collapsing walls? Who can tolerate blindness, how can you reconcile yourself to suicide, how can you live alongside radical amputees and the incurably ill? Who can endure the screams of women in childbirth? There are millions of diseases of the human body, parasites that devour it from inside and outside, supporting diseases of the skin, intestinal occlusions, lupus, tetanus, leprosy, cholera, plague. Why should we passively put up with them, why should we pass by, pretending not to see them, until we are impacted, as we certainly will be? Our minds will suffer, so will our flesh, our skin, our joints. Sores and pus will cover us, phlegm and sweat will drown us, injustice and tyranny will make us bow down, annihilation and impermanence terrify us.

Virgil’s questions go on, and I don’t know the answers to any of them. Though I don’t think I’d join the Picketists, with their signs that say,

“Down with Death!”, “Down with Illness!”, “Down with Agony!”, “Down with Suffering!”, “Protest Pain!”, “Pro Eternal Life!”, “Pro Eternal Consciousness!”, “Pro Human Dignity!”, “NO to Passivity!”, “NO to Laziness!”, “NO to Resignation!”

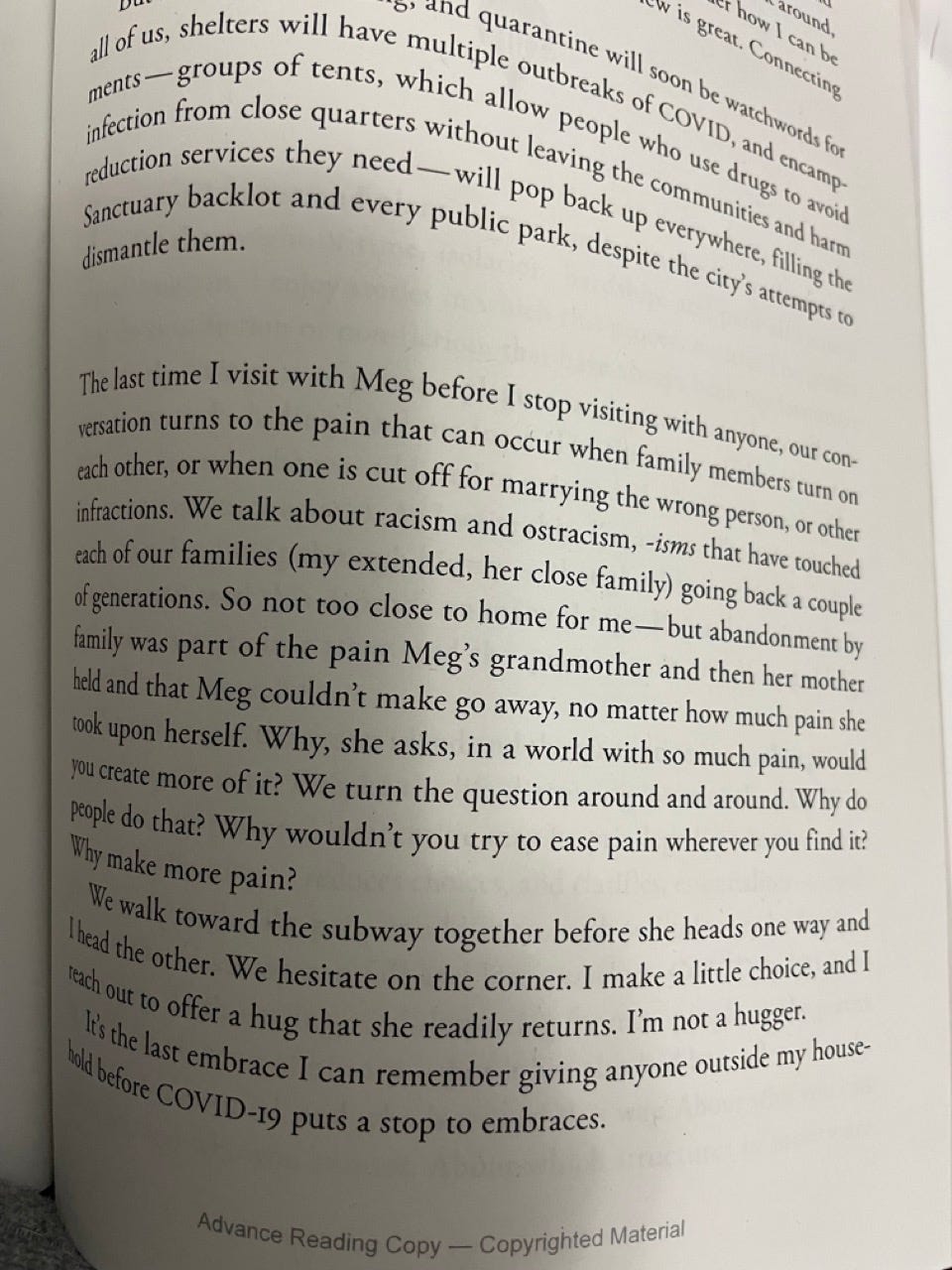

It does, though, remind me of the conversation I recounted in On Opium about suffering, and how much there is, inescapably, in the world, and about why would anyone want to add to the amount of suffering already there?

Now that I think of it, suffering & relief of suffering are of course the themes of this book of mine. But writing it hasn’t brought me any closer to answering these questions.

Let me end with this line (I’ve barely started the book, so there will surely be more) by Kate Zambreno from her pandemic book (not a novel) that looks at the work of parenting and of art and how to think of both of them in a time of precarity. There’s plenty here that isn’t about babies, of course, but as I flip through, this little sentence, about “The baby no one has seen” (because of the pandemic—“We are the only faces the baby sees,” Zambreno writes), leapt out at me for its simplicity, which gives us everything we need:

The baby’s smile, even at 4 a.m., is so radiant.

Friends, I hope this week that you also read much that is eclectic and wonderful, like little shards of painted glass, or tiny mirrors that each reflect a different view of the world around them, to make a colourful mosaic like a kaleidoscope in your skulls.

—Carlyn