The dark earth spins: Friday, Feb 24

The dangers of reading novels; the earth's rotation; Pablo Neruda & friends

Dear Gentle Reader,

Your now-routine quick reminder, as there are more of you every week: On Friday mornings, friends, I send you this miscellany of literary, artsy, and wonder-of-nature goodies to stimulate imaginative thinking. On Sundays, I hope you can stay in bed or ring the bell for the butler to bring you coffee and turn on the internet, then settle in for a good read focused on fiction and living more lives. But please read just what you have time & inclination for: this is about pleasure, not homework.

On communication: you can get in touch with me directly at carly_z@hotmail.com or via Twitter DM (@CarlynZwaren), especially if you have suggestions or wishes for how I might help you LIVE MORE LIVES through fiction. There is also a comments section at the bottom of each post.

And now, onward to Pablo Neruda, libraries and the dark turning of the earth!

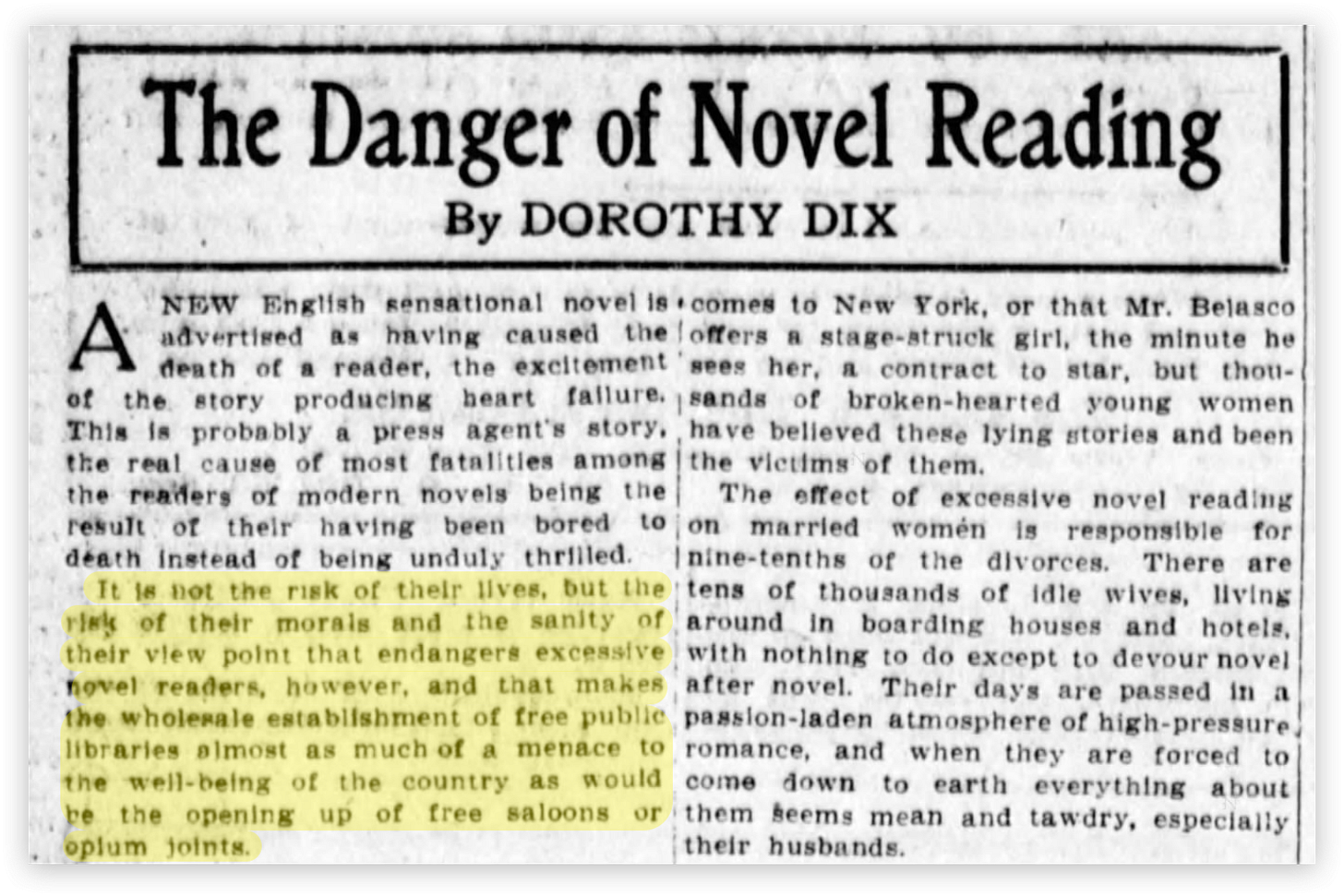

“The wholesale establishment of free public libraries [is] almost as much of a menace to the well-being of the country as would be the opening up of free saloons or opium joints”, wrote popular American newspaper reporter, advice columnist and suffragist Dorothy Dix (according to Wikipedia, at least, she enjoyed a global readership of 60 million people) and was the most highly paid and widely read female American journalist at the time of her death in 1951. She attributed divorce rates to wives’ excessive reading of passion-laden novels (though she also considered the books fatally dull). Here’s the scoop:

OMG since March of 2020 it has felt like centuries pass every year. Turns out that there is at least a partial explanation for this: the days are getting longer! Actually, this paper on variations across decades between the rotation of the Earth’s inner core and its outer mantle is mind-blowing in many ways, not least in that I am learning things those of you who are astronomers or physicists must have known all along, like that leap year seconds must be regularly communicated to the relevant authorities around the world.

I suppose that’s only logical. But it sounds deeply, suspiciously science fictional to me. Not because it’s scientifically amazing, actually, but because of the quaintly Victorian tone of the salutation by which the Paris-based data service addresses said authorities. It might come from a work of Jules Verne or H.G. Wells:

“To authorities responsible for the measurement and distribution of time”.

“News”—at last—about the death of Pablo Neruda half a century ago. Followed by a long and tangled story of famous connections or degrees of separation, and artists & writers getting up to no good—all culminating in some poetry by Neruda, because art outlasts them all.

Neruda was murdered. The great Chilean poet has been, finally, found to have died by poisoning following (and presumably by the architects of) General Augusto Pinochet’s September 11, 1973 US-backed, right-wing coup-d’état. Pablo Neruda’s death in hospital twelve days after the coup was considered suspicious from the start (officially, he’d died of prostate cancer and associated malnutrition), but it has taken all these years for the truth to come properly to light.

The violent overthrow of Salvador Allende’s democratically-elected socialist government—the first such government in the Americas—has been, for Chileans in Chile and in exile since ‘73, their “September 11th” avant la lettre. As Pinochet’s soldiers bombed the tear gas-and-smoke-filled building from fighter planes that day, and others stormed the palace, Allende shot himself using an AK-47 Fidel Castro had given him years before. Neruda had served under Allende, who was a friend, as ambassador to France, before returning to Chile due to poor health.

Neruda, a great poet and a humanist who wrote a wide variety of lush love poems, stirring political poems, and clear, beautiful odes to ordinary people and about ordinary things (“Ode to the Onion”; “Ode to a Large Tuna in the Market”; “Ode to my Socks”), has fallen into some deserved disrepute of late. This is in part due to recent attention to his own account (in his memoirs, published posthumously almost fifty years ago now) of his un-humanist act of raping a woman in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in 1929 or 1930. She was a Tamil maid responsible for disposing of human waste from his hotel and others on the street. He was a diplomat representing Chile in between postings in Burma (Myanmar) and Java (Indonesia). Here is a thoughtful letter written “to” Neruda by Robina Marks, the outgoing South African High Commissioner to Sri Lanka and the Maldives, on what would have been his 116th birthday in 2020, addressing all of this, giving the woman the name Thangamma, although my quick search hasn’t turned up any other sources for her name.

Every story quickly links up with other stories and other characters. In this case, there are many, including artists and writers who were swept up despite themselves, or who wilfully leapt, into the tides of history. Here are just a few more of them: Through his life, Neruda served as honorary consul or diplomat in several other countries, including Spain, where he met Federico García Lorca, another socialist poet eventually murdered by fascists.

Neruda also appears to have been involved in the attempted assassination of Marxist revolutionary and Stalin critic Leon Trotsky, when, as Consul General in Mexico City, he issued a visa to Mexican muralist (and Stalinist) David Alfaro Siquieros. It was in fact Siquieros who had led the attempt on Trotsky’s life, which occurred some three years after Trotsky and his wife Natalia came as exiles to Mexico, first staying with fellow Communist and muralist Diego Rivera, who had convinced the president to offer refuge to the couple, and with his wife, the artist Frida Kahlo. Trotsky and Frida went on to have a passionate but fairly short affair, after which they remained friends. She portrayed herself in a painting dedicated to him that was later admired by French surrealist writer André Breton. After the attempted assassination (one of several), in which Rivera was briefly considered a suspect, Neruda’s visa authorized Siquieros, rather than facing trial, to leave Mexico in order to paint a mural in Chile, where he stayed for a spell in Neruda’s home. Frida and Diego eventually became Stalinists, like Siquieros, and stopped corresponding with Trotsky. Poor Trotsky survived the artist-led assassination attempt (along with his 13-year old grandson, who was shot in the foot)—but was stabbed to death with an icepick a few months later by another assassin, a Spanish agent of Stalin’s NKVD (although Joseph Stalin then wrote that this assassin of Trotsky was himself a dangerous—no kidding!—Trotskyist), and so the man spent twenty years in prison in Mexico with no intervention from the Soviet Union.

Also in Mexico, Frida Kahlo, this time, was brought in for questioning in relation to the murder. Trotsky’s granddaughter, Nora Volkow, has, since 2003, been the director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse in the United States. Volkow and Kahlo both appear in my book about drugs and pain, although I honestly did not expect when I started this that writing about Pablo Neruda here would lead me back there…

Although knowing about Neruda’s self-confessed rape adds (yet again) to ambivalently queasy feelings about unabashed romanticism—the fear that it might be always just about a man idealizing women so he can not look real women in the eyes, that it might be nothing but a gorgeous cover for violence and abuse of power—it does not destroy it for me, because despite that queasy feeling I think there’s still enough evidence that blowsy romantic feelings are felt by all sexes and most gender identities, and by great poets and non-rapists alike. And because, while Pablo Neruda’s humanism may have been selective, as humanism sometimes seems in practice, the emotional experiences the poems express are universal.

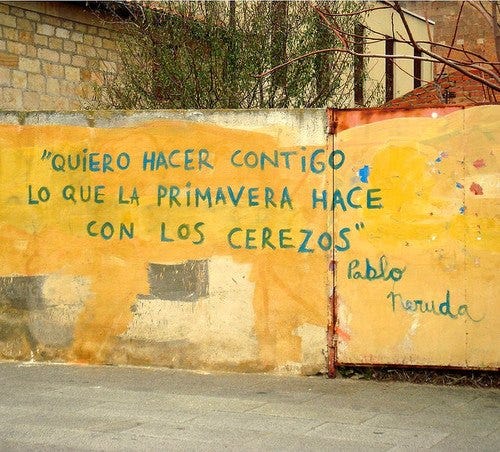

Neruda wrote (my translation):

I want to do with you what Spring does with the cherry trees.

(Let’s assume that whatever Spring and the cherry trees do with each other, it’s consensual and enthusiastic.)

Neruda wrote, in One Hundred Love Sonnets: XVII (translation by Mark Eisner),

I don’t love you as if you were a rose of salt, topaz,

or arrow of carnations that propagate fire:

I love you as one loves certain obscure things,

secretly, between the shadow and the soul.

I love you as the plant that doesn’t bloom but carries

the light of those flowers, hidden, within itself,

and thanks to your love the tight aroma that arose

from the earth lives dimly in my body.

I love you without knowing how, or when, or from where,

I love you directly without problems or pride:

I love you like this because I don’t know any other way to love,

except in this form in which I am not nor are you,

so close that your hand upon my chest is mine,

so close that your eyes close with my dreams.

I note that the last word of the first stanza is soul, the second is body, and the third is dreams. I don’t know if this is intentional on the part of the translator; the original has different breaks, such that the first stanza ends on soul and the second on tierra (earth).

Night on the island (translated by Donald D. Walsh), similar in its confusion of the speaker and his lover (a characteristic of several of the poems in Neruda’s collection Los versos del capitán) has always been important to me in its more resonant original Spanish:

All night I have slept with you

next to the sea, on the island.

Wild and sweet you were between pleasure and sleep,

between Fire and Water.

Perhaps very late

our dreams joined

at the top or at the bottom,

up above like branches moved by a common wind,

down below like red roots that touch.

Perhaps your dream

drifted from mine

and through the dark sea

was seeking me

as before,

when you did not yet exist,

when without sighting you

I sailed by your side,

and your eyes sought

what now—

bread, wine, love, and anger—

I heap upon you

because you are the cup

that was waiting for the gifts of my life.

I have slept with you

all night long while

the dark earth spins

with the living and the dead,

and on waking suddenly

in the midst of the shadow

my arm encircled your waist.

Neither night nor sleep

could separate us.

I have slept with you

and on waking, your mouth,

come from your dream,

gave me the taste of earth,

of sea water, of seaweed,

of the depths of your life,

and I received your kiss

moistened by the dawn

as if it came to me

from the sea that surrounds us.

The Chilean novelist Isabel Allende is Salvador Allende’s niece. In 2013, in an interview with Amnesty International about the murdered president, the murdered poet, and the 17-year military dictatorship that followed, she noted that, after all those years of terror, “soon Pinochet will be just a name to frighten children in bed-time stories”.

And so the dark earth spins with the living and the dead.

Till Sunday, friends,

Carlyn