The Four Seasons: Friday, May 5th, 2023

And the stories of the night shift, of existential dread,

(you can click on the title above to view this on the Live More Lives website)

And other fours: a literary exploration

Dear Gentle readers, hello!

It is my pleasure to introduce the May Live More Lives logo by our resident artist:

You will please note that this gorgeous bird is reading On Opium: Pain, Pleasure, and Other Matters of Substance. If a toucan, you can too!

You’ll find my second book at the public library if you’re in Canada (there are a bunch of copies floating around in the different library systems but you’ll most likely need to order it in to your local branch). You can get the audiobook pretty much anywhere in the world; I didn’t narrate it myself but it is read by the very talented Christine Horne.

I have found that reflecting on the changing seasons feels like a very natural thing to do when writing a regular essay. Some suitable music, of course:

Here is some suitable, if obvious musical accompaniment—in a nice version.

As I thought (again) about how to best structure a ‘miscellany’—although I know, the whole point of a miscellany is that it’s miscellaneous, but I crave more structure and so must bend my self-imposed rule—I realized that I was thinking in fours, inspired by those four seasons that structure the year, especially in temperate climes, and the rhythm this seems to give to my writing of this newsletter. The four humours, the four ancient elements, the four seasons, the four suits of a deck of cards, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. The Sign of Four?

If you want a real literary number, of course, three’s your man. As I explain in the first email you receive from me when you subscribe, groups of three and patterns of three are pervasive in literature, and for very good reasons that we will look at another week.

But having started to think in quaternary terms, I find I can’t stop. I know next to nothing—yet—about any possible role for the number four in literary/fictional content. Or structure. Or experience.

So, it will be interesting to learn about it together. Just to note—unless there is a compelling reason for a number to be considered ‘special’—as I think there is for groupings of three in stories—I’m not into it. Numerology and its associated pseudosciences are only of interest to me when they

seem to intersect with some sort of material reality

have what seems to me a plausible psychological relevance, or

offer something of aesthetic value.

Let’s see what we can glean from a first quick tour through the number four.

The dystopian four

In 1984, George Orwell writes that “Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two make four. If that is granted, all else follows.” In Animal Farm, Orwell again shows his liking of the number four:

FOUR LEGS GOOD, TWO LEGS BAD, was inscribed on the end wall of the barn. … When they had once got it by heart, the sheep developed a great liking for this maxim, and often as they lay in the field they would all start bleating “Four legs good, two legs bad! Four legs good, two legs bad!” and keep it up for hours on end, never growing tired of it.

From the Met’s page on Dürer’s famous woodcut, here is the biblical passage that inspired it (from Revelations 6:1-8):

And I saw, and behold, a white horse, and its rider had a bow; and a crown was given to him, and he went out conquering and to conquer. When he opened the second seal, I heard the second living creature say, 'Come!' And out came another horse, bright red; its rider was permitted to take peace from the earth, so that men should slay one another; and he was given a great sword. When he opened the third seal, I heard the third living creature say, 'Come!' And I saw, and behold, a black horse, and its rider had a balance in his hand; ... When he opened the fourth seal, I heard the voice of the fourth living creature say, 'Come!' And I saw, and behold, a pale horse, and its rider's name was Death, and Hades followed him; and they were given great power over a fourth of the earth; to kill with sword and with famine and with pestilence and by wild beasts of the earth.

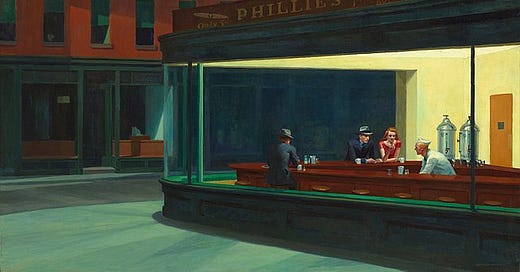

The most surreal time of day

And then there is the eerie poetry of four am. In A Short History of Everything, Bill Bryson compresses the history of the earth into a span we can more easily grasp, to understand the proportions:

If you imagine the 4,500-billion-odd years of Earth's history compressed into a normal earthly day, then life begins very early, about 4 A.M., with the rise of the first simple, single-celled organisms, but then advances no further for the next sixteen hours.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Live More Lives to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.