The first thing I actually wanted to write about for this newsletter—and eventually, for the actual book about literature and experience I’ve been working on, contractions and expansions of these weekly or twice-weekly essays—was adventure, pure and simple. It is the basic spirit of adventure that brings me and probably most people to novels in the first place, and to adventure we return for sheer reading pleasure.

The magical ability of novels is to allow us to experience all things that can be described. In this way, an ordinary person may have experiences as rich and varied as it’s possible to imagine: these can include travels impossibly deep under the ocean, to distant planets, through time, across bodies or species or forms, or to universes that bend the laws of physics.

For advice on the writing of adventures that may be meaningful to us as readers as well, we can go to no better source than Robert Louis Stevenson.

Stevenson’s exotic, Romantic settings and stories with “freakish” elements like evil uncles, one-legged pirates, and fiendish, two-sided doctor/murderers should not, writes Michael Schmidt (in his excellent, 1172-page monstrosity of a ‘biography’ of the novels, which is currently building my biceps) “mask the fact that his essays and fiction lead deep into experience.” Stevenson’s account of the writing of Treasure Island—a family affair, in which he read what he had done during the day to his parents each night—is delightful, and suggests to us that imaginary adventure grows well from a secure and encouraging base. The story gradually unfolding caught his father’s fancy in particular:

he not only heard with delight the daily chapter, but set himself acting to collaborate. When the time came for Billy Bones’s chest to be ransacked, he must have passed the better part of a day preparing, on the back of a legal envelope, an inventory of its contents, which I exactly followed; and the name of ‘Flint’s old ship’—the Walrus—was given at his particular request.

Stevenson used ‘psychical surgery’ to come up with the immortal character of Long John Silver, stealing a good friend—“an admired friend of mine (whom the reader very likely knows and admires as much as I do)”, he writes—and stripping him of all his finer qualities, leaving only “his strength, his courage, his quickness, and his magnificent geniality” and then translating that familiar character, whose psychology he can convey as a full-blooded human’s because he really is based on a real person, into the culture of sailors and pirates.

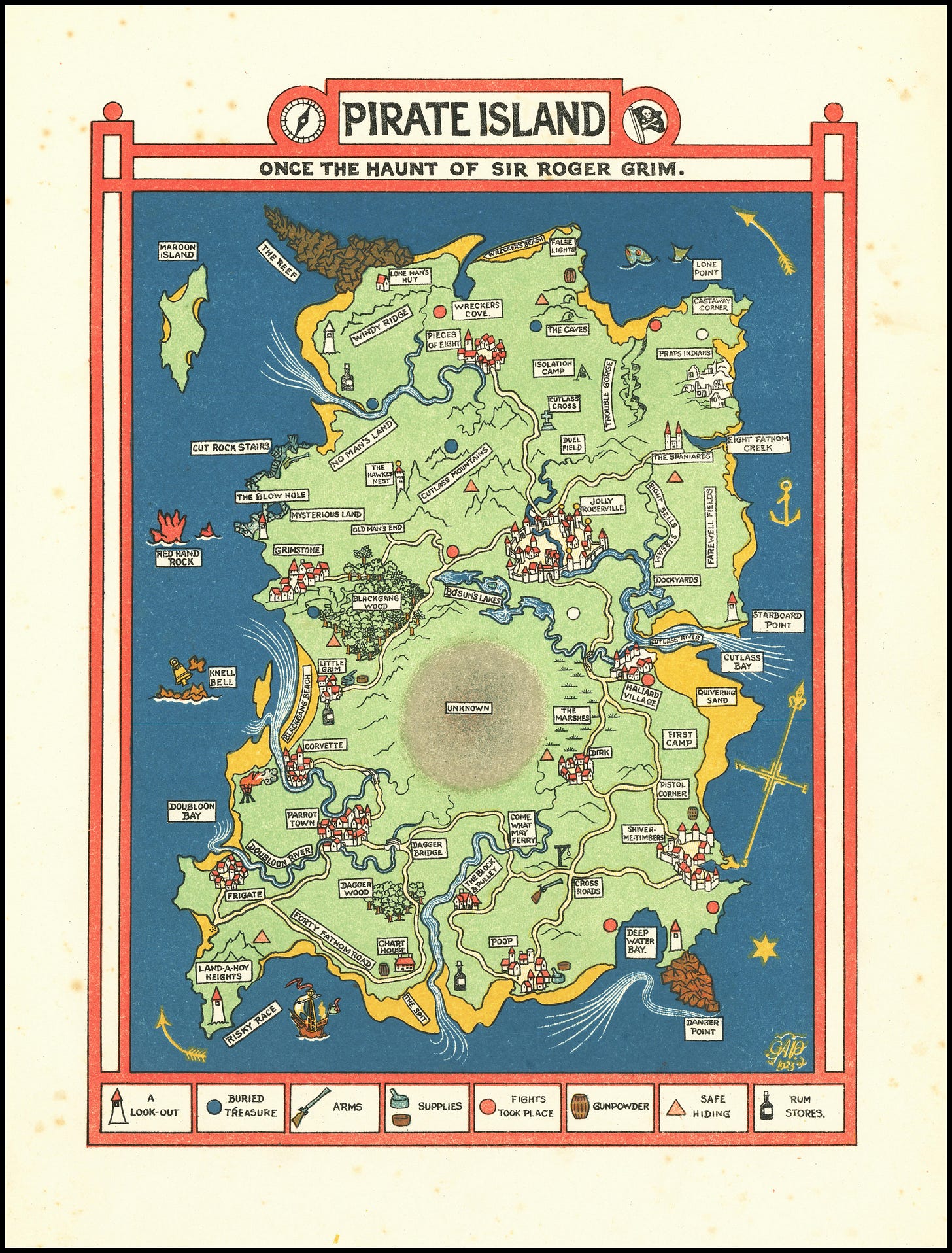

The embrace of the family was important in several ways. Stevenson’s poor health and the damp air forced him to spend much of his time indoors in a holiday cottage, thus distracted from a planned project in which he and his wife would collaborate on a book of stories (due to tuberculosis Stevenson was forced to transmute a proclivity for real life adventure into adventure through the imagination; tuberculosis and frequent illness pushed him to work urgently, the spectre of Death always hovering nearby). An unnamed schoolboy (his future stepson) had come home for the holidays and needed entertainment—in fact, he soon turned one of the rooms into a ‘picture gallery’ of his watercolour paintings, and Stevenson joined him at the easel, coming up with a map. A map of islands, shipwrecks, and a buried treasure.

Looking back at the gestation of Treasure Island, the great writer of adventures and ‘romances’ (including the Gothic horror of Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde) suggests drawing a map of the territory of your story, even if you’re not writing about pirates—because it moves you from one plot point to the next, making difficult choices for you or creating unexpected situations. “The map was the chief part of my plot,” he explains, elaborating:

But it is my contention—my superstition, if you like—that who is faithful to his map, and consults it, and draws from it his inspiration, daily and hourly, gains positive support, and not mere negative immunity from accident. The tale has a root there; it grows in that soil; it has a spine of its own behind the words. Better if the country be real, and he has walked every foot of it and knows every milestone. But even with imaginary places, he will do well in the beginning to provide a map; as he studies it, relations will appear that he had not thought upon; he will discover obvious, though unsuspected, short-cuts and footprints for his messengers; and even when a map is not all the plot, as it was in Treasure Island, it will be found to be a mine of suggestion.

A family friend provided the resonant title—it was originally to have been called The Sea Cook. That title did have the merit of highlighting the especial importance, among the characters, of Long John Silver, who held that role on the Hispaniola, the Squire Trelawney’s schooner. The Hispaniola, of course, is the ship on which Squire Trelawny and Dr. Livesey, taking on the narrator—the boy Jim Hawkins—as cabin boy, and a hired crew including Captain Smollett and the well-respected, charismatic one-legged cook, set out in search of treasure buried on Skeleton Island in the Caribbean Sea.

Properly-speaking, the Hispaniola ought to have been a brig, but Stevenson felt he lacked the knowledge or skill necessary to ‘command’ such a ship and that a schooner better suited his literary sailing abilities. Stevenson finished his book alone, on Davos, where his doctor recommended he spend the winter for his health, taking solitary walks and at one point despairing of being able to build on the first sixteen chapters, which came so easily, to reach a satisfactory end. Of novels, compared to short stories, which he thought anyone might write, Stevenson wrote drily: “It is the length that kills.” The map helped move things along and forced digressions and twists—two harbours in the picture, for example, send the Hispaniola on an extra adventure under the pirate Israel Hands.

There are other useful things we can learn about the reading and writing of adventure from Stevenson’s work and the lucid, honest essays he has left us about the work of writing and the joy of literature (he admits frankly to borrowing—he uses the word ‘plagiarism’, even—elements from other writers: “no doubt”, he says, the skeleton is from (Edgar Allan) Poe, the parrot from Robinson Crusoe (Daniel Defoe), and much of the first chapters from bits by Washington Irving. Yet he defends himself: “no man can hope to have a monopoly of skeletons or make a corner in talking birds”). For writing adventure, Stevenson tells us (via a letter he wrote to Henry James), he had two rules:

War on the adjective

Death to the optic nerve

Although writers of his day indulged in endless visual description (this reminds me of skipping rudely over entire pages of very beautiful description as I tore through Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne books and her Emily series and others), Stevenson recognized that too much of it blocks forward motion and limits the reader’s freedom to imagine out the scene, and thus to imagine themselves into it. Better, in his view, to provide just enough description, leaning not on the visual sense but on others more felt, more imagined, to give us the feeling and reality you want to evoke.

Despite my poor visual memory for faces, I feel like I have a strong sense of what I would have seen in Treasure Island—or in Stevenson’s other classics, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Black Arrow, and Kidnapped, which I especially love—and yet if you get out the books you will see that it’s true. He waged war on the optic nerve (not excessively) and the result is that we are immersed completely in the story, not seeing it from outside as with a picture or a movie. What we think we see is what we imagine the characters must have experienced, using all of our (or their) senses, not only sight. Emotions, too, lie under the surface, discerned mostly by characters’ actions and their tone, as in real life.

There’s nothing like reading a good adventure. You can spend hours immersed in story, driven to keep turning pages through a long afternoon while a gorgeous day goes by, unappreciated, outside, or to keep turning pages for an hour or two after midnight when you had fully intended to get to bed well before. Most important to this drive is the desire to know what is going to happen next. Recently two books gave me this purest of reading pleasures: Little by the Edward Gorey-ish American writer Edward Carey, and The Shape of the Ruins by Colombian writer Juan Gabriel Vásquez. Neither would be described as primarily an adventure by most people—there’s none of the sailing talk of the Swallows and Amazons series (by Arthur Ransome) I loved as a child and that my eldest son loved in his turn, no survival in physically extreme conditions in nature.

Although the adventure novel still exists in its original form (human vs. nature, survival and solitude under extreme conditions, travel, exotic settings and colourful characters, all aspects of the pure adventure novel I continue to treasure) the forward movement and a sort of clarity that characterizes it has been translated into the detective novel, the thriller, the spy novel, and many other genres including fantasy and the disaster novel (and now, specifically, the climate change or post-apocalyptic novel). In a sense, I’m conflating the idea of adventure with that of the well-told, conventionally forward-moving, plot-dependent story. The genre boundaries are necessarily blurry—after all, Stevenson moved easily among several while maintaining his characteristically forward-moving plots and adventuresome feel. Who’s to say that the borders of a pirate’s treasure map must define the adventure story, or that the page-turning tale of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde doesn’t count? That Stevenson novella in fact also fits into numerous genre categories: Gothic horror, as noted above, but also detective fiction, mystery, psychological thriller, even science fiction.

Don D’Ammassa suggests that a quick pace, and the central importance of danger, characterizes the adventure story, thus allowing for overlap between adventures and stories in many other genres:

... An adventure is an event or series of events that happens outside the course of the protagonist's ordinary life, usually accompanied by danger, often by physical action. Adventure stories almost always move quickly, and the pace of the plot is at least as important as characterization, setting, and other elements of creative work.

Thus he believes that Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities is an adventure, because the protagonists are in constant danger of death or imprisonment, while his Great Expectations is not, because danger is secondary, serving only to advance the main plot, which is not itself an adventure. Wikipedia’s first definition, before introducing D’Ammassa’s ideas, is even broader: adventure excites the reader or presents danger.

Sticking a bit closer to D’Ammassa’s assertion about threat to the protagonists, who have somehow fallen out of their ordinary lives, we can include novels with greatly unconventional, modernist or post-modern hijinks. Laurent Binet’s HhHh, for example, is a moving and satisfying adventure novel alongside its successful meta-fictional aspects, which question historical truth and try to resist romanticizing a story whose elements are intrinsically dramatic.

Some good stories here on my bookshelves that have the character of an adventure include:

True History of the Kelly Gang, by Peter Carey

The Horseman on the Roof by Jean Giono

Life of Pi by Yann Martel

Anansi Boys by Neil Gaiman

Gregor the Overlander by Suzanne Collins

Ahab’s Wife, or The Star-Gazer by Sena Jeter Naslund

Papillon by Henri Charrière

The Life & Times of Michael K by J.M. Coetzee

Other recent adventures that promise good things: Salman Rushdie’s Victory City, The Last Wolf, by László Krasznahorkai, Amitav Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies and the rest of his trilogy. Not new, but I’m curious to find out if it merits the title of an adventure despite all sorts of literary tricks in it, is The Last Samurai, by Helen DeWitt. Also not new, James Clavell’s Shōgun. And Foucault’s Pendulum by Umberto Eco. Like The Last Samurai, it’s an intellectual adventure, and by now a classic of postmodern literature. I haven’t read it but am reading Eco’s Numero Zero right now and enjoying it very much—it has enough forward movement to imagine that Foucault’s Pendulum may be all its admirers say it is. I also hesitate to include Olga Tokarczuk’s Books of Jacob as I haven’t read it yet—so am not sure if it illustrates Stevenson’s idea of the adventure as I’d like—and its daunting size means it might not be the best introduction to her dazzling work. But in trying to figure that out, I came upon this wonderful interview with Tokarczuk, which you may enjoy without having read her writing (yet).

There is so much more to say about adventure writing, and more to work through. As I struggle with a mystery novel, even post-first draft there are bits that still don’t work or connect properly. Every change I make vibrates through the entire structure, making it wobble dangerously and require shoring up so it doesn’t collapse. By contrast, the adventure story I was working on before is a clear sequence of events with no doubling back or complicated scaffolding (I left it part-done to take up the mystery when the one book I was working on split excitingly, though perhaps fatally, into three possible novels, in three different genres). When I return to the adventure, I’ll pay close attention to Stevenson’s advice and insights on that genre, which have stood the test of time. Although these insights are relevant to all fiction where you hope to truly enthrall the reader.

Which of course I do hope. I do.

With that, I wish you all a week where every little action contributes to an overall feeling of adventure (the best kind only); the weather we expect this week in Toronto at least is very suitable for adventures outside. I’m setting out right now in good company, pocket knife packed, and a map printed out from Google, for a hike (photo above taken after I wrote these words). When the kids were younger everything was an adventure. Stevenson’s trick was “the singular maturity of the expression that he has given to young sentiments”1. And also his “buoyancy, the survival of the child in him”2.

-Carlyn

In Henry James’ words, as cited by Michael Schmidt.

As writer and fairy-tale collector Andrew Lang put it.

Share this post