TGIF (Thank God It's Fiction): Friday, Feb 10

Today's miscellany is mostly about material traces

Dear Gentle Reader,

Did the Thought-Fox1 come this week? Perhaps we might use this poem as a secular prayer, a useful superstition reserved for atheists like me, believers, and cautious agnostics alike—just so long as we all seek willing suspension of disbelief in the service of fiction. Happy Friday, friends!

Welcome, new Readers! On Friday morning you get this miscellany of literary, artsy, and wonder-of-nature goodies to stimulate imaginative thinking (majority voted to keep it to Friday; we’ll revisit this in time as it’s a lot of weekend reading I still think could be better spaced-out). On Sundays, then, I hope you can stay in bed or at worst just crawl out in your pyjamas to make some coffee, then settle in for a good read focused on fiction and living more lives. But please read just what you have time & inclination to read: this is for pleasure, not homework, and you should take just what you want from it.

I have spent nearly twenty years making wishes come true as the hard-working associate of the Tooth Fairy, the Valentine’s Fairy2, even Santa Claus! I love granting wishes, with no nasty surprises (typical of wishes in fairy tales) in return. SO, if you have wishes for how I might help you LIVE MORE LIVES through fiction, please get in touch with me directly at carly_z@hotmail.com or via Twitter DM (@CarlynZwaren). Note: feedback is also welcome but may not include the Truth about any of the above-named characters: as mentioned above, we all agree to suspend disbelief here in the interest of enchantment.

And now on to today’s miscellany. I hope that some bit of poetry or image or piece of text will startle you this week, strumming your heart’s secret chords or sparkling through your synapses.

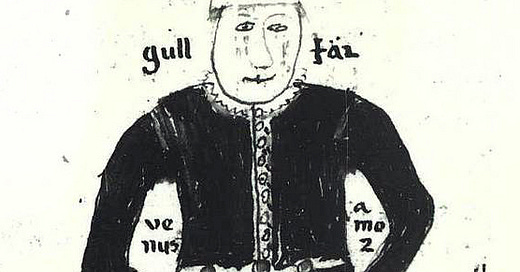

For me, those sensations often come from art and literature that is dark, enigmatic, and beautiful in a stark way. This week I came across a painting by Abraham Neumann, a Polish Jew, on Facebook, where there is a group called Degenerate Art that shares works by artists considered ‘degenerate’ by the Nazis. Some of these artists went into exile or survived the concentration camps. Others were murdered in the Aktion T4 program I mentioned last week, at Auschwitz, or, in Neumann’s case, in the Kraków Ghetto (he was executed—or murdered—there in 1942). It was his birthday as I wrote this on Monday, so seemed like a good time to share this seasonally-appropriate, emotionally-freighted painting, created sometime before 1930.

I believe that a minority of people simply have too much, that it’s neither earned nor deserved, nor sustainable. That much of the material luxury in the world is simply obscene in the face of misery and unjust distribution of wealth. That, for various reasons, these are incompatible with survival of the great diversity of life on Earth. Given all this, I feel a bit… not guilty or bad, but awkward, say, about my full-on, undeniable love of aesthetic and material beauty.

César Aira reassures me a little on this point—mostly because it’s good to hear that others feel the same need to justify their love of things, as he does in the very short book Artforum. Aira, an Argentinian writer whose work was nominated for the Man Booker International prize in 2015, has published literally over one hundred very short books, most under 100 pages—here’s a list of 72 of them (I dunno what happened to the rest but I suppose after my first fifty or so novels, I might start to get a little careless too). Aira’s protagonist in Artforum, a man obsessed with an American magazine called, yes, Artforum, has just found and purchased twenty-four back issues of it, and a friend gave him a “rare and beautiful pen”, made of gold and porcelain, with two little buttons of black coral. All this on the same day! He tells us:

One can say they are only material objects, that other things bring true happiness. but would that be true? There always has to be something material, even love needs something to touch. And in my proceeds of that joyful day, the material was so entwined with the spiritual that it transcended itself, without ceasing to be material. I won’t talk about the pen, I would get too carried away. But that transcendence was pretty obvious in the magazines. They were paper and ink, and they were also ideas and reveries. They reproduced the dialectic of art, with as many or more attributes as art itself. Before, I spoke about the “material trace.” It was more than that: the word is “luxury”. Material made of spirit is the luxurious border where reality communicates with utopia.

I recently made the happy discovery that while stiff joints have for the past few years made it difficult for me to write quickly by hand as I used to do constantly as a journalist as well as for other writing, fountain pens are so smooth that it takes much less effort. So I’m returning a little bit to writing by hand. And I have to report—though I’ve resisted temptation so far—that there are some very beautiful fountain pens out there. I promise not to hoard them or use them to write anything that will move the world further away from that ‘luxurious border’.

Speaking of fantasy and materialism, here is sci fi author Cory Doctorow writing in the New York Times about fantasy writer (and London School of Economics PhD in international law, and founding member of the Left Unity party in the UK) China Miéville’s new book, the excellently-titled A Spectre, Haunting: On the Communist Manifesto, which is a work of non-fiction about exactly what its title promises. Addressing Miéville’s fiction, though, Doctorow writes:

His fantasy novels are shot through with class struggle, and in ways that are integral to the narratives. Novels like “King Rat” (1998) aren’t gripping phantasmagoric thrill rides despite their politics; rather, it’s the politics that imbues them with so much excitement and conflict. It turns out that class war is a hell of a plot device.

To be honest, I have had trouble getting into Miéville’s fiction for reasons I don’t understand, as they seem wonderful—the politics really are part of the story and there is no polemical heaviness to it. That isn’t the issue. Nor is the writing, which is very good, nor the characters. Sometimes—not always—it’s not them, it’s me. There are so many novels to read and so little time that I feel no guilt about abandoning books…but in this case I think I ought to try again. Some just need the right reading conditions or moment in your life to ‘work’. Here at home, I have a copy of Miéville’s The Last Days of New Paris, about an alternative 1950s Paris where Nazis are still occupying the city and the Resistance must contend not only with them but also with monsters that are (literally) Surrealist artworks come to life. I was enjoying it but somehow trailed off into something else. I also mean to get hold of his multi-award-winning The City & the City, which I think could be instructive as I tackle my own mystery set in a dystopian city.

Lloyd Alexander portrays this extremely dramatic, novelistic aspect of real life—class struggle, of a kind—in his fantasy novel trilogy, Westmark. The second in the series, The Kestrel, is my favourite. In it, the protagonist, a former printmaker’s devil named Theo, gets caught up in a war in which monarchists and revolutionaries work together—temporarily. Here two other characters unwittingly discuss Edmund Burke’s political theory:

“The records show it was barefaced thievery.”

“Undeniably common land,” said Torrens, “but it was added to the principal estate, La Jolie, two generations ago.”

“Thievery doesn’t count if it’s big enough and old enough? Montmollin already has more acres than anyone can keep track of. Add them up, he likely owns half of Westmark. Well, this much he’ll have to give back to his tenants, no matter which of his noble ancestors stole it.”

“Beyond a doubt, this should be done, said Torrens. “But not hastily. It is not the moment. I urge you to act with greatest deliberation.”

“Delay, you mean,” said Mickle. “If it’s an old grievance, the more reason to set it right as soon as possible.”

Westmark, the books all written in the early 80s, is marketed as a young adult series. It addresses important issues imaginatively, with humour and colour3 and vivid characters, and in a clear and beautiful style, making these novels as suitable and enjoyable for adults as for children. Many young people’s books are actually better-written and less in need of a firm editor than their bloated, poorly-structured, or impenetrable adult counterparts. I might mention here if a book we’re discussing is YA or adult, but would never discriminate in my own reading, and suggest you don’t either, so long as you’re not sticking to kids’ books out of avoidance of ‘adult’ content (in which case…have you read good YA? It can be intense!) or more complex language (in which case I can happily suggest some great books to bridge the gap).

And finally, here, freshly published, is the second story in the trilogy of articles I’ve been working on about intersections between drug policy and the environment. It has nothing to do with fiction—unfortunately. Your support for LIVE MORE LIVES, through which I escape with you into fiction, will also help me continue doing this work in the world of reality. Please share it, as well as this newsletter, far & wide!

Till Sunday, friends,

Carlyn

click the link to see last Friday’s newsletter, scroll down to the end to read the marvellous, hushed poem in question.

yes, there’s a Valentine’s Fairy? Did no one tell you? Perhaps she’ll make a late appearance next week…

thank you again for enduring my Canadian spelling, dear American neighbours.