Dear Gentle Readers,

I lost it only near the end of +972 Magazine’s horrifying, carefully documented article about what appears to be a concentration camp where Palestinian prisoners are kept blindfolded and where the unspeakable concept of the Kapo has been re-invented as “the Shawish” (Hebrew-speakers among the Gazan prisoners who are not blindfolded but forced to act as subordinate captors, bringing their blindfolded fellows to the actual Israeli soldiers for punishment). The quote that made me finally fall apart in the article, linked above, wasn’t from one of the many accounts of beatings, deliberate humiliations and torture perpetrated by Israeli soldiers, acting according to policy and practice condoned and encouraged at the highest levels in Israel right now, but these perversely tender words of Ayman Lubbad, a legal researcher at the Palestinian Center for Human Rights:

“My [3-year old] son really wanted to go to the zoo, but there is no zoo [left] in Gaza. So I told him that on my trip* I saw a fox in Jerusalem — & indeed, when I was interrogated, in the mornings, some foxes passed by. I promised him that after it was all over, I would take him to see them too."

*The ‘trip’ was Lubbad’s detention w/o trial, under a hastily-developed law reminiscent of the infamous 90-day detention law in apartheid South Africa. “During his detention, Lubad1’s wife told their children that he had traveled abroad; Lubad isn’t sure they believed it,” because the toddler saw him stripped of his clothes on the street that day, writes Yuval Abraham, the Jerusalem-based journalist who wrote this brain-exploding, heart-crushing article.

During this ‘trip’, Ayman Lubbad and his younger brother (who was also eventually released, but then killed almost immediately upon returning home by an Israeli shell that struck his neighbour’s house) experienced and witnessed torture, routine and exceptional humiliation, and death due to reckless and inhumane treatment. And stomach-turning instances of human inhumanity to other humans, such as this:

According to the testimonies, the Palestinian detainees from Beit Lahiya were loaded onto trucks and taken to a beach. They were left bound there for hours, and another photograph of them was taken and circulated on social media. Lubad recounted how one of the female Israeli soldiers asked several detainees to dance and then filmed them. [bolded text in horrified emphasis is my addition]

The detainees, still in their underwear, were then taken to another beach inside Israel, near the Zikim army base, where, according to their testimonies, soldiers interrogated them and severely beat them. According to media reports, members of IDF Unit 504, a military intelligence corps, carried out these initial interrogations.

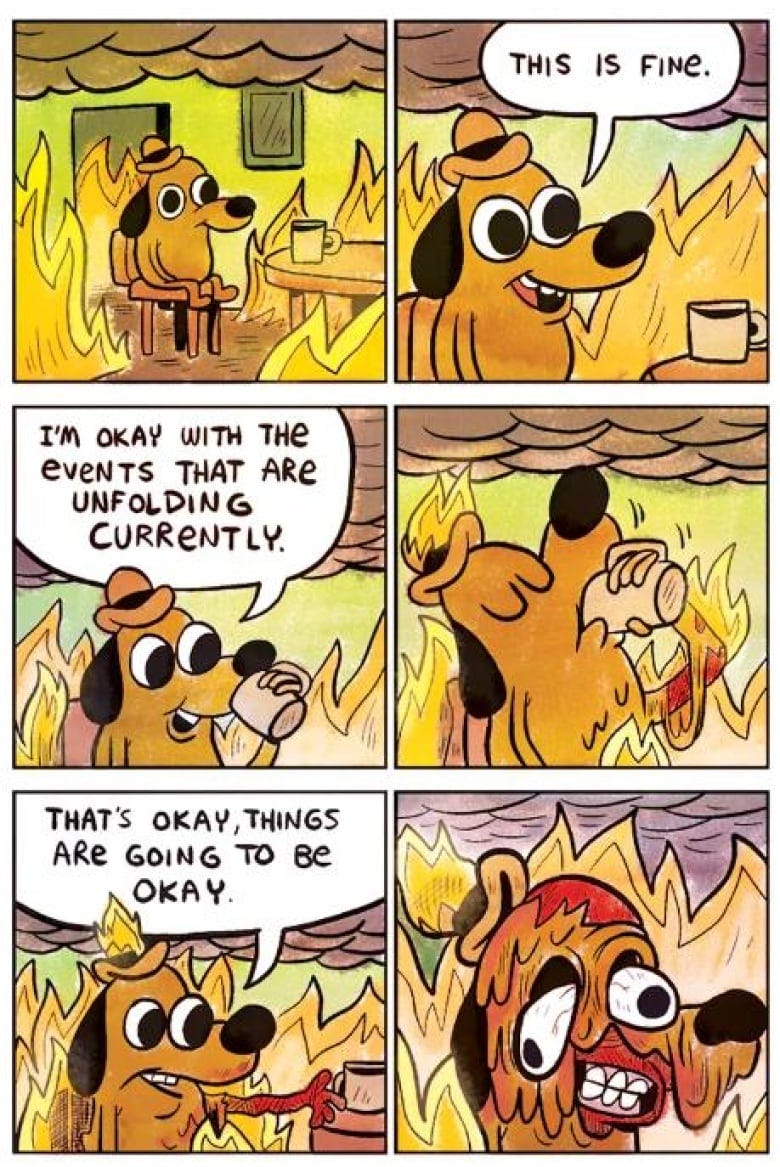

I wrote the above words about Yuval Abraham’s article in +972 on January 5th (and the rest of this newsletter ten days later), so I wouldn’t forget it in the flood of horrible things I keep learning. They each seem to glare brightly at first and then fall like leaves which eventually blend together on the ground. The impression left is one of horror, but as with every other event that we witness from afar, the details fade, because we are not experiencing them directly, at least, those of us who don’t have families or friends and colleagues in Gaza are not.

Is it possible that we can read about such atrocities as these and then forget them? Is it possible that we can let the individual names, the agonizing details, the particular awareness of dignity and suffering fade into an undistinguished mass of bad things? Is it possible that, if we’ve paid enough attention in the first place to gain a moral conscience and a sense of the unbearable urgency since Israel began its retaliation for the October 7th massacres two days later, that feeling can fade?

Of course it can, just as people can fade from alive to dead over these weeks and months. It is surreal to watch it happening, but it happens.

Perhaps the human ability to turn from suffering, both deliberately among those who fear that being around suffering will contaminate them with it, and also simply because of our limited abilities to hold geographically-distant information in our heads, and our human boundedness to a forward-moving timeline, where life just doesn’t stop because it ought to, because justice demands it… perhaps this combination of human failings and the laws of physics and the limitations of our psychology together explain the puzzling disconnect between fiction that appears to demonstrate the highest possible commitment to human rights, and the writers of it, many of whom seem so uninterested in taking a clear stand in favour of such rights in the real world. Or so craven about it.

(As you know, I’m on an intermittent publishing schedule here at the moment. Or you may have just joined me here on Substack—welcome! Don’t worry, I will be back more regularly eventually. At that point I will be grateful if you decide to become a patron of my work as a paid subscriber. That’s not possible for anyone right now, and current paid subscriptions are on hold so no one is charged during this sabbatical of sorts—I’ve given myself till spring to finish or make really substantial progress on the novel I’m trying to get done.

For now I welcome you and hope you will spend some quality time browsing in the ample archives of Live More Lives (I’ve just removed the paywall on sixty-four essays—enjoy!). Please tell your friends so we can continue nourishing our little root ball or bulbs of readers through the slow hibernating days of winter, to be ready for spring.)

I’ve always found myself especially, and often unbearably, moved and distressed, in writing and in life, by anything involving the pain of those unable to fully understand what is happening. This means, typically, cruelty to children or to animals. For somewhat similar emotional reasons, another thing I find unbearable is deliberate humiliation of others. As with the attack on innocence—as with the child who longs to visit the foxes in Jerusalem, not grasping it’s the site of his father’s torture, and there being only rubble and corpses where once there was a zoo in Gaza—humiliation involves irony, which of course is how writing wrings emotion from us, and how life brings us to tears.

In the case of humiliation, irony arises through the mental juxtaposition of the heinous act—being forcing a prisoner to dance, to wear a pair of underwear on their head, to eat food that is forbidden in their religion or to submit to sexual innuendo or simulated or actual sex—with the normal, wholesome activities being mimicked and desecrated, which are human and joyful activities, like dancing or sex or eating or practicing one’s religious rites.

Fundamentally, it is sickening—the gravity of the situation keeps driving me in search of new adjectives, and I find I resort to words like sickening or stomach-turning as I try to characterize the wrongness of it all—that Palestinians should be forced to perform their suffering in hopes of enough protest abroad that the United States will finally put an end to this outright, or that they or other funders of Israel’s retaliatory war, like Canada, a war that has turned a traumatizing massacre into an opportunistic excuse to attempt to erase Gaza and its people, take over its land, sea and resources2, consolidate right-wing policies and domestic reduction of democratic space, and let loose a vast repository of hate against Palestinians, wherever they are and whatever connection they have or don’t have to Hamas, and whatever their desires for national liberation, or civil rights, or life itself.

And yet, those of us who are paying attention to the individual voices of Gazans are mostly doing so on social media, which puts us in the impotent position of watching and sharing posts as we are moved to do so. Until South Africa’s righteous case at the International Court of Justice (soon to be followed by actions against the United States and the United Kingdom for complicity in genocidal acts), at least, as it changes the tone if not significantly changing our role.

I don’t think writing poetry is ‘performing’ suffering. Mosab Abu Toha is a Palestinian poet whose youngest child is an American citizen. Abu Toha was a finalist for the (American) National Book Critics’ Circle Award and is the founder of the Edward Said library in Gaza. Here is a poem, apparently the whole thing, that he shared on Twitter:

The scars on our children’s faces will find you. Our children’s amputated legs will run after you.

This is a writer speaking in the most haunting of terms out of his intimate experience. The suffering performs itself, becoming a curse. Or perhaps just an end to impunity.

By contrast, much of the writing that has most marked me, or that marked me at an impressionable age of coming to some level of political consciousness, has come from South African anti-Apartheid writers, largely white and educated in a Western (and anglophilic) tradition, who questioned that political system by understanding it as an extreme but perhaps natural or inevitable outcome of colonialism, and placing against it small-l liberal values, which they acquired from reading literature from that tradition and its critics.

Here, from J.M. Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians,

One thought alone preoccupies the submerged mind of Empire: how not to end, how not to die, how to prolong its era. By day it pursues its enemies. It is cunning and ruthless, it sends its bloodhounds everywhere. By night it feeds on images of disaster: the sack of cities, the rape of populations, pyramids of bones, acres of desolation.

Coetzee’s narrator, the unnamed Magistrate, represents the Empire but, stationed at a distant outpost, far from the imperial centre, faced with the cruelty of its emissaries, he comes to empathize with the ‘barbarians’ under his rule:

I know somewhat too much; and from this knowledge, once one has been infected, there seems to be no recovering. I ought never to have taken my lantern to see what was going on in the hut by the granary. On the other hand, there was no way, once I had picked up the lantern, for me to put it down again. The knot loops in upon itself; I cannot find the end.

Liberalism has proven to be fatally flawed where it has provided cover for an increasing rightward shift in values over decades, where it has cynically ignored issues of power and class, where it has turned into the sentimental wrapping on a neoliberal Trojan Horse of a gift. Coetzee’s Magistrate is, other than his brief personal rebellion, unable to move from empathy to the solidarity that brings people together to force change. Instead, he simply watches, describing the shame of his own inability to understand.

Despite the hamartias3 of liberalism, I stand by some of its fundamentals: human rights are universal and indivisible. Being a writer, like being a human, requires the courage to see beyond parochial concerns to acknowledge and defend every human being’s right to life.

With just about every day that has passed as I’ve gradually written this newsletter in fits and starts there has been some dramatic event involving mass death, indescribable suffering, further erosion of international norms, and increased existential risk (in very different ways) to both Palestinians and Israelis, and indeed all of us as Israel, the US, and others who seem to enjoy playing with fire, in fact seem bent on blowing us all up before global heating can roast us alive. We could be using this time so much better.

In this (ha ha) climate, it’s nevertheless been lovely taking time to focus (to the extent I can focus at all) only on novel-writing and a little bit of journalism. Many of the difficulties I’ve had with the novel have related to the question of how to position myself in relation to suffering and to marginalization. It was a fruitful problem for my first books. In fiction the issues are different but overlapping. I still haven’t figured it out. But I’m writing at a good clip.

I hope to write more about the experience of working through this, and other aspects of this novel in progress, next time.

Till then, I wish you much reading and much noticing.

-Carlyn

seems to have been spelled wrong in the article. I’ve left it as Lubad in the quotes.

off-shore oil, which foreign companies are very eager to develop, though it’s not clear for whose benefit although American rhetoric has it funding a revitalized Palestinian Authority on a mythical ‘day after’ the war, while others are incoherent but scary, and no one with power to act seems interested in what Palestinians think.

tragic flaw OR tragic error, depending on your interpretation (usually understood to be a tragic flaw dooming a character from the start, as in the Greek tragedies, but the other ways you can understand it might—or might not—be suitable here) . There’s an overview of interpretations of this interesting word here on Wikipedia.