Dear Gentle Readers,

Reality is an ever-present ghost at our banquet of literature. Switching analogies, we sit beside—or within, wet-footed or drowning—a constant poisonous stream of terrible news1, some involving awful coincidence and much of it involving systemic injustice, corruption, and the long shadows of history. All of it individually painful. Right now, though, we will consciously set the tragedies and atrocities and crawling anxieties of real life aside, just here, just for a moment, to focus on those that amply populate fiction. Here, the worse things get for your protagonist, the more enjoyable it is for your reader.

*note that today’s newsletter includes discussion of suicide (because it’s about poets Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes, and their unhappy families). It’s in footnote 3 if you would prefer to avoid it.

Ok. Today’s ‘news’ sounds like poetry—it’s about a ‘quenched’ galaxy. Who knew2? To be quenched, in galactic terms, means that you, a galaxy, have stopped forming stars. Wikipedia further informs me, the un-enlightened, that quenching occurs when galaxies lose cold gas. Look at this wonderful quote from an article about the galaxy just discovered, by the James Webb Space Telescope, to have suddenly stopped its star-making 12.5 billion years ago: “We really want to know when the conditions are ripe to make quenching a widespread phenomenon in the universe.” The science is interesting, for sure—but I really just love the language.

An exercise in attention and mental transfiguration, in imaginative alchemy. Is there anything green where you live? Or, given the time of year here at least (I see I have subscribers in Arizona and Alabama where I guess not everything is encased in ice), something withered and brown, but originally alive, perhaps even with life still pulsing, if sluggishly, inside it? You may have heard of forest-bathing (shinrin-yoku).

We live downtown and my living room window looks out onto a parking lot, the backs of restaurants, and usually a random man pissing against a wall. Nevertheless, Toronto is veined with ravines and real nature, as well as the raccoons, skunks, and occasional coyote that wander out into the residential streets. I used to (gently) force my kids through a little stretch of ‘forest’ within the public park near my house for a regular forest bath. I don’t like the self-important self-helpishness of how it’s been adopted as the latest trendy based on an out-of-context, highly marketable concept from [Japanese/Finnish/French/etc etc ad nauseam] culture (though shinrin-yoku as an exercise with a name only dates to the 1980s), but the name is poetic and I actually kind of like giving this title to something—walking in nature—that my parents would have just considered normal life when I was a kid being hauled out on a walk. Not a trend or a virtuous act or Self-Care or Wellness or anything branded. But a little gussied-up.

Anyway, within beeping and vrooming distance of one of Toronto’s main thoroughfares and just paces from the paved path, you can (almost) disappear into the sudden hush created by trees and mulch and untended or barely tended plant life. In this space, time slows down to the rhythm of growing things.

This week, find those growing things. First feel the ground beneath your feet—outdoors, in the hush of a true forest or a little sliver of forest like mine or a garden or in your house or your apartment, which is itself over concrete and inhabited space, perhaps potted plants and old kale curling softly in a neighbour’s refrigerator, and under that there must be soil: soil of good structure, with particles of different sizes—clay, silt, sand—hopefully stable when wet and dry, able to absorb precipitation even when basements flood and rivers overrun their borders. Tiny organisms: bacteria, fungi, and other microbes. Little pockets of air. Dead plant material, broken down also by earthworms and ants. Humus: the waste product of organisms in the soil when they have consumed and excreted dead plants, dead animals, dead matter of all kinds.

Breathe in, and imagine the respiration of soil creatures. Exhale, and imagine the death mulching here as the source of all life.

T.S. Eliot knows as well as the groundhog that (for what it’s worth) spring is on its way:

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

Winter kept us warm, covering

Earth in forgetful snow, feeding

A little life with dried tubers.

In your kitchen, find a little bit of old potato from the stew you cooked last week, the bit that flew from the knife as it hit the cutting board, then launched itself into space and settled in an inaccessible gap beside the stove. This or something equally stunted, dessicated, not enough to support a little life. This is your dried tuber, your dull root, your waste product, your humus-to-be. Meditate upon it, and think of the soil creatures, and the green or formerly green space you visited or imagined and remember that, mid-February or not, six weeks from today will be the last day of March.

Literary romance

I thought that this week we might pause the literary analyses a little to consider a fantasy of mine: the bookish romance. Although I have had the good fortune to experience poetry and straight-out romance in my relationships, to have a relationship with someone supportive of my writing, and to have had relationships3 with people who read (thank God) and even write, I have not had a relationship with anyone who writes for a living, or who reads like their life depends upon it.

As in all romantic fantasy but more so, the secret and unreasonable hope is that the Beloved’s mind will be essentially an interestingly-rearranged copy of your mind. To not crack such a brittle stone idol, you’d need to be able to carry on for months and years, always finding that whatever moves you moves the Beloved with equal intensity, and in the same way.

Beyond the obvious risks of basing a relationship on the purest of fantasies—on fiction!—risks specific to love relationships with fellow writers or intense readers include those that relate to competition, poverty, privacy, division of labour, children, and time. Especially, surely, for women in heterosexual relationships, who, historically at least, have been all too likely to wake up one day like Gregor Samsa to find ourselves transformed into typist, Muse, or monstrous alimony vampire (see: divorce revenge stories by Roth, Kureishi, Carey, Layton, Bellow).

And yet, and yet… the intensity of like-minded souls on a grand adventure! The vision is irresistible, not just to me. I mean, clearly Sylvia Plath found it so:

He sets the sea of my life steady, flooding it with the deep rich color of his mind and his love and constant amaze at his perfect being: as if I had conjured, at last, a god from the slack tides.

Thus she wrote about her husband, fellow future 'leading-poet-of-their-generation’ Ted Hughes, in her journal, as quoted in biographer Helen Clark’s Red Comet: The Short and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath. Finally, the marriage of true minds.

But Sylvia’s diary draws a far less harmonious portrait of the couple’s second honeymoon, in Cape Cod. From the start, things went badly. There were annoyances. They had no car. They had nosy and noisy neighbours. There were horseflies, and a lack of basics in their cottage, things like coffee mugs, pillowcases and eggbeaters. While Ted worked on poems that would become his second collection, the writing, for Sylvia, wasn’t going well; she hadn’t published a story in a magazine in five years, and she worked worriedly on four short stories during this time that were never published, trying to make them slicker, smoother, more mature (one became the germ of what grew into her novel, The Bell Jar). Clark quotes Plath vowing to

never get in this rusty state again, for writing is the prime condition of both our lives & our happiness: if that goes well, the sky can fall in.

Holding on to their own—individual goals and successes, inner solitude in which to achieve them, private emotional space—was the basis of both her happiness, she felt, and theirs as a couple. (Preserving his own internal space proved far easier for Hughes, though, for various reasons relating both to individual temperament and to societal sexism and misogyny.4) Rainer Maria Rilke wrote on this, when he asked in his poem Love Song (translation here by Stephen Mitchell)

How can I keep my soul in me, so that

it doesn’t touch your soul? How can I raise

it high enough, past you, to other things?

I would like to shelter it, among remote

lost objects, in some dark and silent place

that doesn’t resonate when your depths resound.

Yet everything that touches us, me and you,

takes us together like a violin’s bow,

which draws one voice out of two separate strings.

Upon what instrument are we two spanned?

And what musician holds us in his hand?

Oh sweetest song.

In Wind, Sand and Stars (Terre des hommes in the original French), his memoir of the 1935 plane crash that inspired his classic The Little Prince, author and aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote that “Love does not consist of gazing at each other, but in looking outward together in the same direction.”

And indeed, as Clarke writes,

Each afternoon, after four hours of writing, Sylvia and Ted biked to the shore. There, they swam along a sandbar halfway between Nauset Light Beach and Coast Guard Beach, with “clear level water & long rollers.” The sand and the blue horizon stretched in both directions for miles; Sylvia had fantasized about such summer afternoons during the long Cambridge winters. In the evening, they read.

Gazing in the same direction, yes. But this idyll, even as she lived it, had little hold on her creative life. Instead, she wrote a poem about a couple at odds (as she did during their first honeymoon, in Spain), this time about the meaning of an Ouija board’s messages: “I glimpse no light at all as long / As we two glower from our separate camps, / This board our battlefield,” says the wife. And despite this being their honeymoon, Plath’s internal focus was on her own ambitions and her own anxieties: “My life, I feel,” she wrote, “will not be lived until there are books and stories which relive it perpetually in time.”

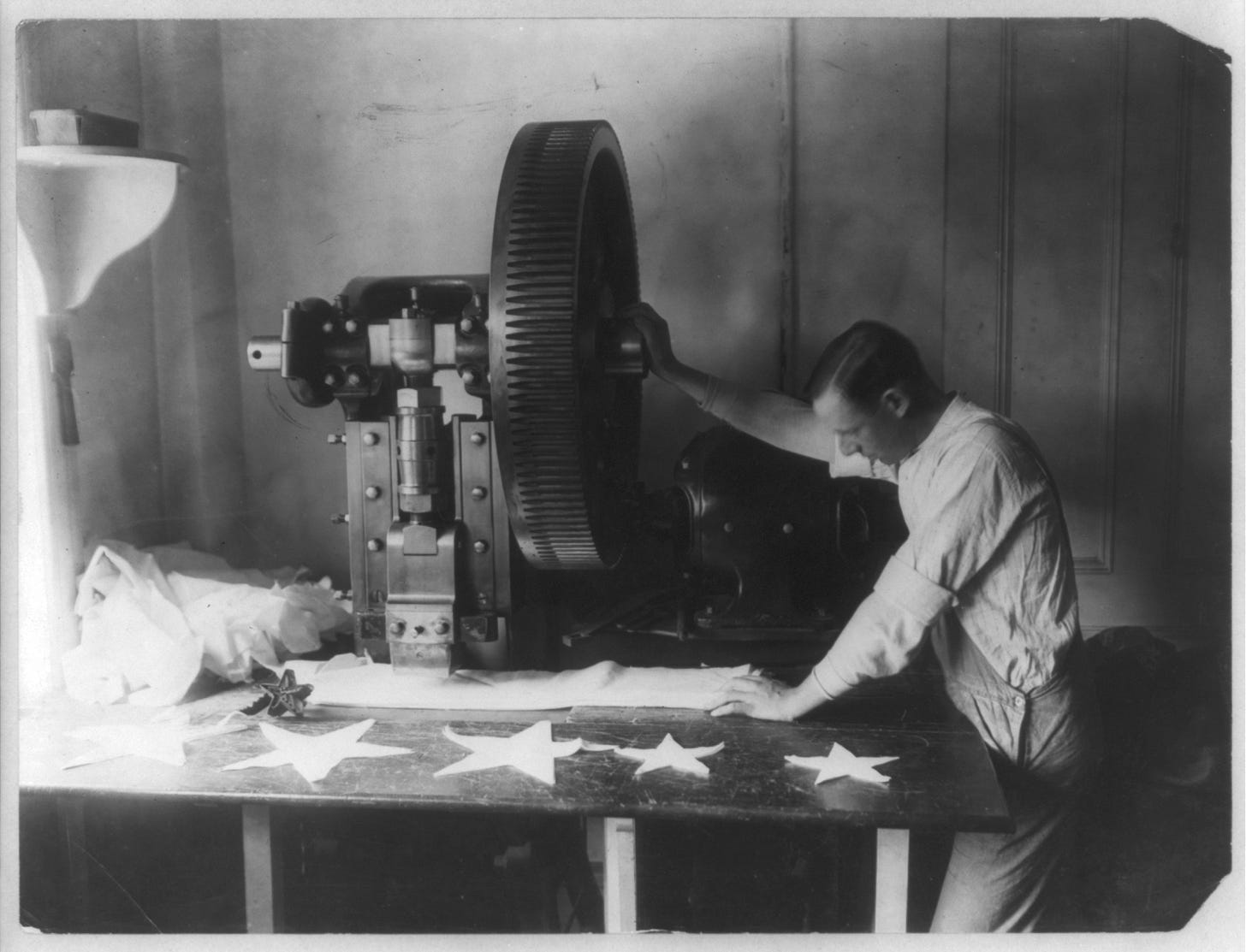

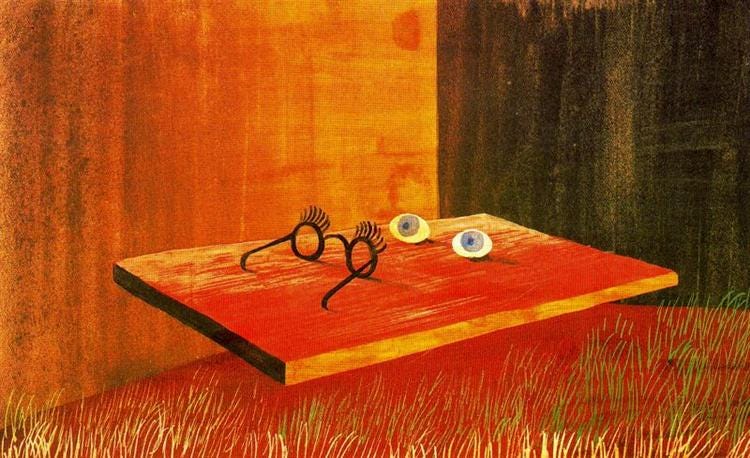

In search of a novelistic portrayal of peaceful literary relationship, I looked up from my desk, beside my single bed, and scanned the bookshelf: nothing. I googled all over the place. I searched for The Guardian’s top 10 lists of the Best Scenes from Novels of People Reading the Newspaper While their Significant Other Writes Poems by the Fire. Or Goodreads’ list of Best Romances Involving Couples Contentedly Sharing Cookies While Ignoring Each Other, Eyes on Their Own Pages. Nothing and nothing. How can this be? In fact, I am absolutely positive that if I spent longer searching I would find these classic scenes of happy couples reading in the dozens. The thing is, though, that they would of necessity be brief—because they would not be very exciting. Unfortunately for them, Plath and Hughes’ relationship was all too exciting, all too novelistic. A good novel, you’ll recall from the image at the top of this page, is one that torments its protagonists from start to finish with building intensity. Hardly the recipe for a happy relationship, nor for a peaceful life.

Wonderful, supportive relationships between writers, and passionate reader couples do exist, of course. But if what we really want is inhumanly perfect, telepathic understanding, a book’s probably a better bet than a writer. And if what we’re really after is romance—intense experience based in fantasy—books, rather than writers, are where we’re likely to find it.

Have a good week, friends.

Carlyn

Don’t shoot the messenger, mind you: it’s not the reports that are toxic, nor the reading of them or the act of listening to them, nor the sorrow or anger they provoke in sensible and decent people, but the existence of these all-too-often preventable miseries and sorrows. An important distinction.

Yes yes, astrophysicist and astronomer friends, you knew.

This doesn’t actually add up to more than a couple of relationships. Heck of a lot of overlap.

These have been well-chronicled, by him and by many, many others, since Plath sealed off the kitchen to protect her sleeping children, then stuck her head in the oven, the first of Hughes’ two partners to die by suicide—Assia Wevill, the writer and translator for whom he left Plath, was the second. Wevill killed their four-year old daughter when she killed herself. Hughes married a non-writer in 1970 and they were still, it seems, happily married when he died of a heart attack in 1998, while being treated for colon cancer. Frieda and Nicholas, Hughes and Plath's two children, grew up to become, respectively, a poet/painter and a biologist specializing in salmon ecology. Nicholas, the scientist, killed himself in 2009. More recently evidence has emerged that Hughes was not ‘just’ heartless but also physically abusive. Plath haunted him all his life, and his last collection of poems was about her. The last line of Birthday Letters: "But the jewel you lost was blue".