Dear Gentle Reader,

Earlier this week I was thinking of diversity, not in the ‘woke’ or ‘politically-correct’ sense1 but in the novelistic one: diversity of content, structure, style, and methods of creation. But somehow as I started writing about the incredible capaciousness of novels, I was distracted by one set of examples I wanted to use, the novels-about-novels of Spanish novelist Enrique Vila-Matas, two of which broke into my apartment from the nearby library this week and kept me up late last night. And then, of course, one thing led to another.

I ended up thinking less about how the novel form is defined by the way no definition seems able to fully contain its vast possibilities, and more about two specific models or approaches to writing of all kinds: the digressive and the constraint-based. Or, if you prefer, the hyperlink or the handcuffs. Though these seem almost like opposites, they are more companionable than that, and I certainly use the handcuff approach to create some order in my naturally-digressive writing. Just thinking about constraints in writing can all too easily lead you from one thing to another, wandering from that topic to something else, tangential. Meanwhile, constraints, cages, limitations, handcuffs, and other rules and restrictions rein in excessive digression in the interest of:

getting to the point;

being coherent and satisfying; and

finishing things.

Starting with a pretty pamphlet poem I have by Anthony Etherin, an experimental poet in the UK, I soon made my way to the internet, where I got a good reminder of just how well the internet mimics my own digressive mind. As you’ve surely noticed, my thinking-in-writing ambles and wanders. The writing—whether it’s journalism, Twitter posts, literary essays, fiction or emails—proceeds by an inefficient process of accumulation and intercalation, in which I figure out what I want to say in the process of saying it. This then needs to be reined in by strict editing and formal or thematic constraints after the fact, making me more of a pantster (writing by the seat of my pants) than a plotter (writing from an outline from the start).

When I don’t take substantial time to go back over my writing, I produce difficult monsters. My family and friends can attest to this: texts with an excessive number of subclauses, parenthetical statements that forget what they are parenthetical to, and direct messages I’ve accidentally hit ‘send’ on while still editing, a new phrase or idea clearly visible where I tried to hide it inside the old one. I’ve learned over time to (mostly) make it work. My favourite part of writing, actually, is the harsh editing phase. It is then that a half-glimpsed idea seems to me to take shape via the correct arrangement of text and white space on the page, a visually appealing set of lines and silence: a Morse code of incoherent or choppy ideas tapping out a more logical and elegant flow.

Although the more I give in to this intuitive way of preparing a literary dish, the slower I get, I believe in it because the accumulation and intercalation result in a richer stew of examples, images and ideas. Cooking the books, so to speak. The trick is to make sure that after accumulating and inserting detail you then refine, remove and smooth out. And to ensure that the tightrope walk of lightly connected ideas (to switch metaphors again) eventually leads to secure ground by eliminating parts that don’t, in the end, contribute to a coherent and satisfying whole.

But I digress.

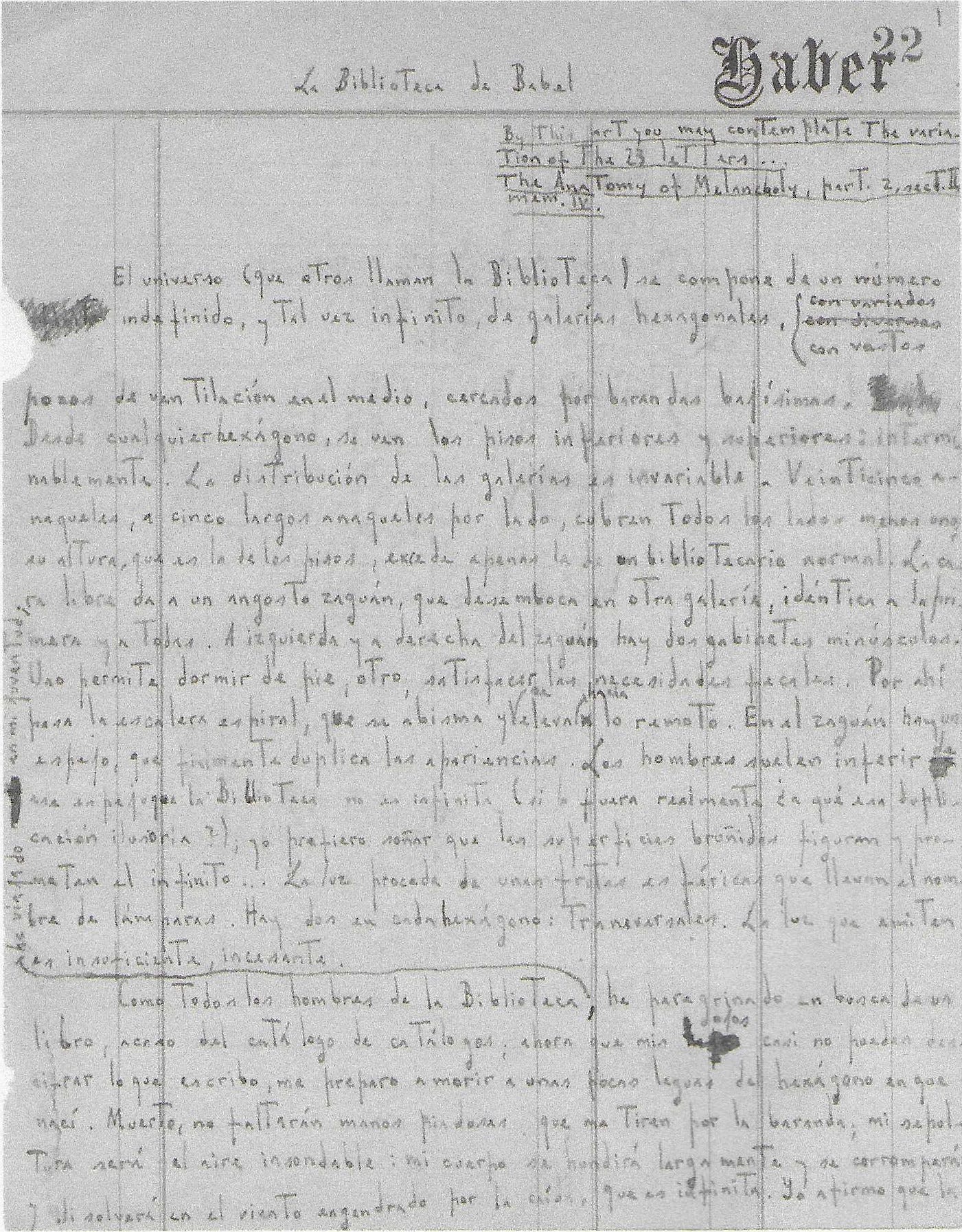

I’m not the only one who’s observed the internet’s resemblance to a mind synapsing or branching its way from thought to thought. As digital media theorist Janet H. Murray notes in this fascinating essay, the varied work of Argentinian writer and passionate reader Jorge Luis Borges anticipates some of the labyrinthine qualities of the World Wide Web—most specifically in “The Garden of the Forking Paths”, which describes a text of infinite possible readings, many years before the invention of the hyperlink:

His fiction evokes a sense of flickering focus, of an individual consciousness constantly reforming itself, of an utterance constantly in the process of translation. Borges confronts us with the “pullulating” moment, when we become aware of all the possible choices we might make, all the ways in which we might intersect one another for good or evil. His imagined Garden of Forking Paths is both a book and landscape, a book that has the shape of a labyrinth that folds back upon itself in infinite regression.

Have you ever sat down to “just check something quick” and woken up centuries later to find your great-great-grandchildren have died of old age and civilizations have risen and crumbled while you were drifting among your own garden of forking, hyperlinked paths as one interesting thing leads to another?

In the world of the forking path garden, time does not move forward at all, but outward in proliferating possibilities of creation and destruction that make up the totality of human potential. To live in Borges’s world is to feel complicity and exhaustion, but also wonder.

So one thing led to another, and, having digressed from diversity to constraint and back into infinite possibility, I came upon this article about the 2020 Christopher Nolan movie, Tenet, which I have not seen, and the title of which, you’ll notice, is a palindrome. Lo! The article contains an interview with Anthony Etherin. Here are a couple of his palindromes:

How to Draw a Pyramid:

A zig. Now one Zag. Gaze now on Giza!

and this lockdown-inspired piece:

Put it on.

Knot it up.Walks a man,

in a mask….Law:

Put it on.

Knot it up.

Constraint-based poetry is much like other less extremely-described formalism (a sonnet is a strait-jacket that liberates, a corset that embodies, a pair of handcuffs but also their key). And even non-poets are familiar with palindromes, writing that can be read the same way forwards as backwards. They don’t occur only in words. There are number-based palindromes, genetic palindromes, date palindromes, classical music palindromes. The palindrome I started in the title of this post (not Etherin’s—the internet seems evenly divided in blaming English poet W.H. Auden, and Scottish poet Alastair Reid) is not very sleek, but it does at least include a literary reference, and I dare you to do better: T. Eliot, top bard, notes putrid tang emanating, is sad; I’d assign it a name: gnat dirt upset on drab pot toilet.

As well as writing palindromic poetry, Etherin has messed with or merged existing forms (creating, for example, the anagram sonnet), and creates entirely new forms, such as the aelindrome, which sounds like a very light camel, or like those thin blue pages that folded in on themselves to make their own envelope and which my generation’s parents used to fill with weekly letters to their parents overseas.

The results of these highly formal constraints can be startlingly lovely. As Etherin puts it, each work reaches “in spite of its shackles, for melody, imagery and meaning.” If you’d like more, I’d recommend Stray Arts (and Other Inventions), which explains in detail how and why he comes up with the fiendishly clever trellises upon which he grows his poems.

Perhaps I drifted here because formal experiments are on my mind. I just got hold of Raymond Queneau’s Exercises in Style. Queneau was, with mathematician François Le Lionnais, a founder (in 1960) of Oulipo, which stands for Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle—in English, the Workshop for Potential Literature—of literary movements probably the one most associated with constraint-based writing, including of novels.

Speaking of digression (we were, somewhere!), I would like to share a marvellous Tourist Map of Literature that allows you to find other writers similar or somehow related to your own. Type ‘Raymond Queneau’ into the search box and you do in fact get a good set of connections—Oulipo types like novelist Georges Perec, fellow French writers, Surrealists (he was one, briefly), and some surprises like Ovid (Queneau cites him in his novel The Flight of Icarus)—built from data on what other writers Queneau fans have enjoyed. Yes, it’s similar to the creepy recommender functions everywhere online that anticipate what you will enjoy based on what you’ve liked before, thus preventing expansion of your tastes and eliminating random discoveries you would find browsing library shelves. But maybe—because of the visual way it’s presented—it’s more like the sort of digressive reading I’ve been doing lately as I read one author and then see where else their style, social circle, and legacy take me.

Seeking further examples of poets who work with particularly fiendish and interesting constraints, I remembered Etherin’s fellow Houdini-poet, the Canadian Christian Bök. In vain I ransacked my unfortunately un-hyperlinked bookshelf in search of his 2015 work Xenotext: Book 1, which describes his beautifully bananas project to overcome the ordinary limitations we face when we try (as one does) to write poems into DNA, by literally enlisting bacteria as his co-authors. Bök made his name as a poet with the charming Eunoia (2001), a highly constrained book of poems that I also have somewhere in this madhouse of books.

Then, still wandering, I came upon this essay for students, written by Rebecca Hazelton, in which she describes constraints as a way to get over your anxiety about the endless options of the blank page. For me, a mesmerizing sense of possibilities, rather than anxiety, makes it hard not to start, but to finish—until a deadline provides clarifying constraint/adrenaline. Hazelton writes:

As a reader, I enjoy that moment of recognition when the constraint crystallizes, and I see the trick of it. As a writer, I want my poems to delay that moment as long as possible. This is again another opportunity for fruitful frustration and resistance.

And then I came upon Carolyn Forché’s poem, On Earth, a 46-page abecedarian poem based on Gnostic meditations and arranged alphabetically by stanzas where each line of the stanza starts with a single letter of the alphabet. Here’s a bit of L (quoted here):

languid at the edge of the sea

lays itself open to immensity

leaf-cutter ants bearing yellow trumpet flowers along the road

left everything left all usual worlds behind

library, lilac, linens, litany

And then, and then, and then… before all that, actually, your masked crusader correspondent ventured boldly into an IRL theatre—after ensuring that its ventilation system boasts of seven air changes per hour—to see a conceptually interesting and visually nifty play. Here’s a teaser, below (don’t say I never take you anywhere).

It took me longer than my companion to figure out the gimmick. But the striking visual effects will linger. The central metaphor, too. It refers to the need for repair in an ecologically degraded world in which any undoing of what has been done must, surely, be constrained. Ontroerend Goed’s play takes a well-known palindrome for its title: Are we not drawn onward to new erA?

Are we not?

Until Sunday, friends.

—Carlyn

Your now-routine quick reminder, as we speed towards our first 100 subscribers at Live More Lives: on Friday mornings, friends, I send you this miscellany of literary, artsy, and wonder-of-nature goodies to stimulate imaginative thinking. On Sundays, ask your butler to bring you coffee and turn on the internet, then settle in for a good read focused on fiction and living more lives. But please read just what you have time & inclination for: this is about pleasure, not homework.

yes yes, I too am glad that Roald Dahl will not be bowdlerized, though not because I defend every rich, dead white male’s God-given right to call women ‘fat cows’ or worse in any children’s book they please, but because I think it’s a waste of time and readers have the right to know that the man who writes gleefully horrible (& mostly brilliant) stories for children and adults was a gleefully but genuinely horrible person (Dahl about Jews, in 1983: “Even a stinker like Hitler didn’t just pick on them for no reason.” There is more. I have, despite all this, been a fan of Roald Dahl’s nasty writing for as long as I can remember, and especially love his autobiographies, Boy and Going Solo.) On his own feelings about being made palatable to non-misogynist, non-racist readers other than me, I have read both that he threatened his publishers with an enormous crocodile if they changed a word after he was dead, and that back in 1973 he happily submitted to his publishers’ censorship (otherwise known as ‘editing’) by allowing them to whitewash his original racist depiction of the Oompa Loompas in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. For marketing/money-making reasons.

Ironically, the goal here was to make it less objectionable for the publication of its racist-joke ridden sequel, which I loved as a kid, although the bigotry has aged badly, resulting in the cardinal sin of the jokes being not just offensive, but also as un-funny as both movie versions of the book to date (there’s a prequel coming out this year). These were themselves each offensive due to their own unique badness rather than their bigotry, and to his credit Dahl hated the gag-inducingly whimsical 1971 film with Gene Wilder as Willy Wonka. Fortunately for him, Dahl was long dead by the time Johnny Depp’s skin-crawling take on Wonka came out). Now let’s move on to worrying about censorship with a rather more significant impact, like this or this.