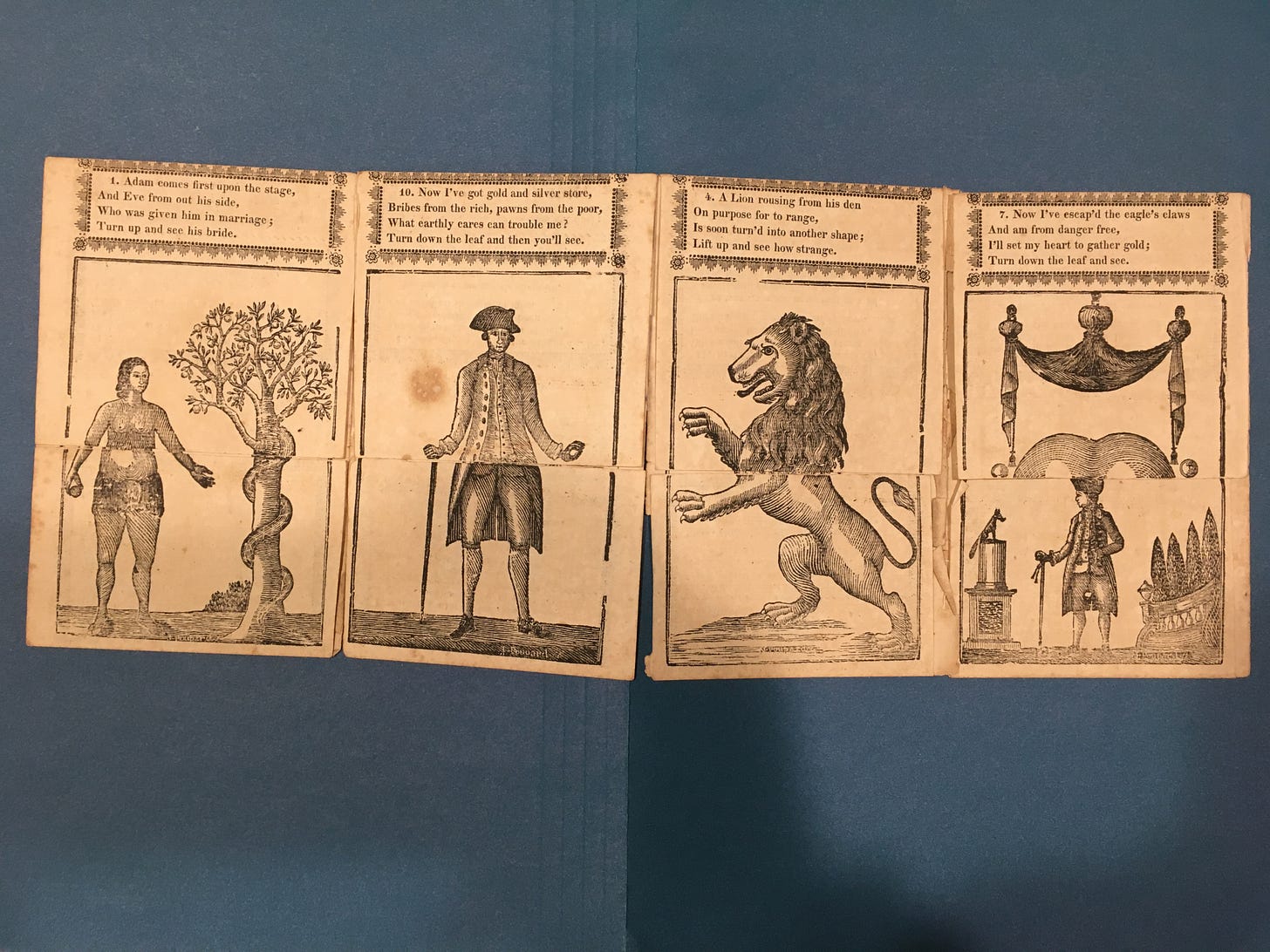

Forms changed into new bodies

On metamorphosis & the literary version of a Vulcan mind meld

I don't remember the hotel, but I know where the street is, I used to live in Lisbon, I’m Portuguese. Ah you’re Portuguese, from your accent I thought you might be Brazilian. Is it so very noticeable. Well, just a little, enough to tell the difference. I haven’t been back in Portugal for sixteen years. Sixteen years is a long time, you will find that things have changed a lot around here. With these words the taxi driver suddenly fell silent.

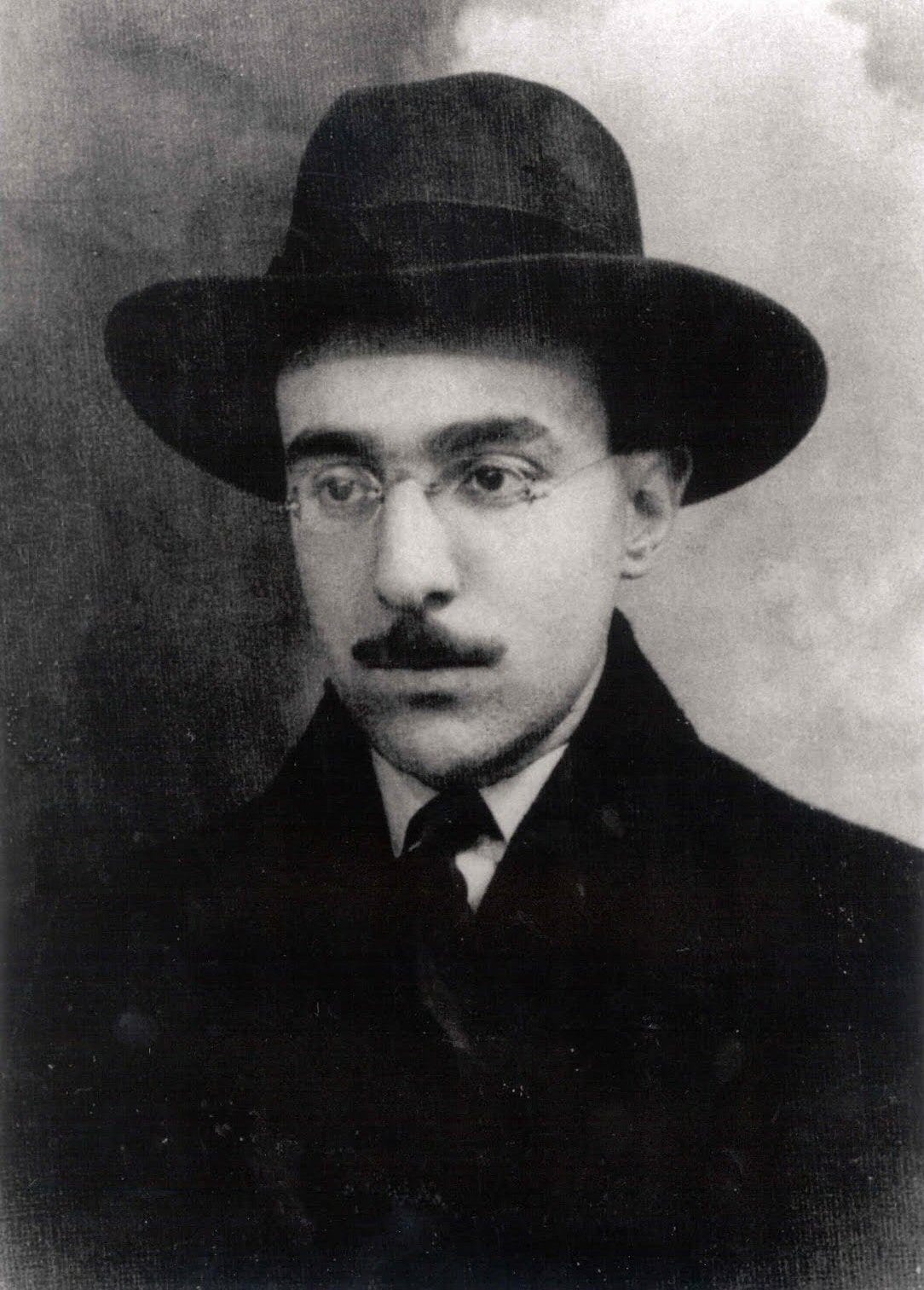

The passenger is one Ricardo Reis, a doctor who returns to Lisbon after a decade and a half in Brazil, as recounted in a novel by Portuguese novelist José Saramago, The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis. Dr. Reis has come back to Portugal upon hearing of the recent death of the real-life Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa. Pessoa, who died in 1935 having barely published anything, was found to have over 25,000 manuscript pages he’d written and stashed in a trunk—brilliant pages. Pessoa—his name means ‘person’—created dozens of ‘heteronyms’, which were not just pseudonyms but distinct persons, characters with their own personality and history who were the purported authors of his different works. Dr. Ricardo Reis is, or was, one of these imaginary authors of Pessoa’s real writing.

It would be hard to say whether Pessoa lent his consciousness to the fictional Dr. Reis, or whether Reis and his other heteronyms endowed the real-life author with their fictional personalities for the purpose of creating the works signed with their names. And what, then, to make of the doubly-fictional Reis in Saramago’s novel, or of the fictional Fernando Pessoa who also appears, despite having died before the start of the book1? I haven’t read The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis, but Saramago (despite his unique writing style that mixes together naivety and folk idioms, omniscient perspective and great subjectivity, with run-on sentences, eccentric punctuation and untagged dialogue, as you see above) is brilliant at bringing you into the consciousness and experience of another person—his incredible plague novel, Blindness, is a perfect example—so I am eager to watch him play with characters of varying levels of fictionalization.

This week I want to write about metamorphosis, and I have two great, resonant sentences (both first sentences, here) from which to choose:

One morning, when Gregor Samsa woke from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into a horrible vermin.

This is, of course, the unforgettable beginning of Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis (Susan Bernofsky’s translation). First Gregor Samsa’s consciousness sits in the body of a man. Then, for no good reason, it is in the body of a sort of beetle, who is treated like vermin as a result of his physical transformation until he no longer believes himself deserving of better. Alternatively, I have this first sentence on change:

Now I am ready to tell how bodies are changed

Into different bodies

That’s from poet Ted Hughes’ really readable, often funny version of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, called Tales from Ovid: 24 Passages from the Metamorphoses (I’ve been reading it aloud with one of my teenagers with some success. In part because the Greek myths behind Ovid’s Roman retelling went over very well when my boys were really young, most especially thanks to this simple and startlingly graphic (the eyeballs, the blood) graphic version. Don’t knock it till you’ve tried it). Physically, first you’re one thing, and then you’re another, and of course your experience, conveyed in writing, is different for each.

One of my favourite books, one that I’m sure I’ll mention often here, is David Malouf’s An Imaginary Life, a slim novel that imagines the inner life of that very same Publius Ovidius Naso in exile from Rome, banished to a distant village by the Black Sea. This is a simple, straightforward, and very beautiful book where the transformations are internal and thematic: it’s about love, new beginnings and ‘civilization’ versus nature. Apparently, as with the surprising number of novels in which people interact with a deceased Fernando Pessoa (two at least just in English translation—see footnote #1), we have here another set of completely original books both built around a very specific premise: a different novelization of the same period in Ovid’s life won the typically astutely-judged Goncourt prize, though I have not seen that one yet.

Themes of metamorphosis are rife in literature, overtly in folk and fairy tales, but everywhere else as well. Change, of course, drives fiction, and if it doesn’t specifically occur not just in the story world but very notably in the protagonist as well, the absence of change may well be a theme, overt or implied. This is the case for example with Vladimir and Estragon of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, and Rosencrantz & Guildenstern, in Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead, and for the characters Jay Gatsby in The Great Gatsby (he’s too bored and rich to change) and Captain Hook from Peter Pan, or the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up ( he is too one-dimensionally evil, despite his interesting fear of clocks).

The concentrated, forward-rushing power of a short story can make it especially haunting, compared to many novels. And the quality of being haunting (which we discussed recently) like the quality of provoking nostalgia (which came up a couple of weeks ago), is one of the things I most cherish in literature: because it stains my mind with the sense of an experience, with all its unsettling and strange particularity. Julio Cortázar’s short story, “Axolótl”, has that quality. It takes metamorphosis from a process of change—as described by the physical and real transformation of a caterpillar into a butterfly, the thematic transformation described by Malouf, and the imaginary transformations described by Ovid and Kafka—to a process of identification. The latter, in which consciousness is passed from character to character, as we may imagine occurring after death, if we believe in reincarnation for example, otherwise really occurs only through fiction.

The un-named narrator of Cortázar’s story (a young man, I think) is fascinated by the axolotls he sees at the botanical gardens aquarium:

The eyes of the axolotls spoke to me of the presence of a different life, of another way of seeing. Glueing my face to the glass (the guard would cough fussily once in a while), I tried to see better those diminutive golden points, that entrance to the infinitely slow and remote world of these rosy creatures.

After fascination comes imagination. What if the axolotls’ awareness were prisoner of their bodies?

I began seeing in the axolotls a metamorphosis which did not succeed in revoking a mysterious humanity. I imagined them aware, slaves of their bodies, condemned infinitely to the silence of the abyss, to a hopeless meditation.

After imagination comes empathy, and pain.

Their blind gaze, the diminutive gold disc without expression and nonetheless terribly shining, went through me like a message: “Save us, save us.” I caught myself mumbling words of advice, conveying childish hopes.

And after empathy comes identification.

So there was nothing strange in what happened. My face was pressed against the glass of the aquarium, my eyes were attempting once more to penetrate the mystery of those eyes of gold without iris, without pupil. I saw from very close up the face of an axolotl immobile next to the glass. No transition and no surprise, I saw my face against the glass, I saw it on the outside of the tank, I saw it on the other side of the glass. Then my face drew back and I understood.

External descriptions let you see or hear or touch a thing, similes let you understand it by comparison, and metaphors give you an unmediated understanding of the thing by identification. First-person narration situates you right there. In On Opium: Pain, Pleasure, and Other Matters of Substance, I tried to bring readers directly into my experience. This is what we do whenever we have a first person narrator2. But we can intensify the feeling. We can use all these devices mentioned above, plus first-person narration, plus moment-to-moment, perspective-bound description to give the reader the sense that they are inside another consciousness (like being trapped in an axolotl’s body, or wearing a virtual reality helmet that allows you to experience not only the external world from the chosen point of view, but the character’s internal world as well). In this way the reader is, in the first reading at least, deprived of objectivity, personal judgment or wider perspective:

Everyone is talking at the same time and their words are rattling around my head, banging inside, shouting back and forth like someone’s playing a mad game of squash in my skill. I feel this sense of urgency, of emergency. It’s an urgent emergent submergence situation. I’m submerged in it, choking. Or I’m a stringed instrument but all the strings are fraying. All seventeen of my lovely children are asking me to do things, listen to things, help with things. All of them at once. Someone has me by one ear, someone by another, and they pull in opposite directions. Please lower your voice, I say, trying to hide the tension as I speak, but the voice is like a fork scraping a plate, a full set of nails scraping a blackboard; someone is throwing their entire weight at my ear drum like a horde of taiko drummers. I just want it to stop, I need it to stop. Stop stop stop. I am a wire and I am going. To. Snap.

Or, more pleasantly: “there’s a pleasant weight on my eyelids, as if I were falling into a dreamless, restorative sleep. At the same time I seem to float, perhaps on a pool raft drifting on saltwater waves, with a sort of inner buoyancy.”

The metamorphosis in which the narrator’s consciousness changes in “Axolotl” isn’t really a metamorphosis, in the end, but, as in literature, more of a transfer. Here it is, complete. “He”—the narrator’s consciousness—is now a prisoner in the axolotl’s body. The narrator must now observe his former body in the third person:

Weeks pass without his showing up. I saw him yesterday, he looked at me for a long time and left briskly. It seemed to me that he was not so much interested in us any more, that he was coming out of habit. Since the only thing I do is think, I could think about him a lot.

As an exercise today, consider where you might send your consciousness so that it can report back in writing on the experience. Could you place it in the skull of your partner, your child, a friend? Could it exist in a particular tree, distant Venus, a carton of milk? What would be most interesting? What would be trite, or unbearably saccharine? What would be emotionally challenging to imagine and write? What would be entirely new, an experience conveyed in the first person that has never been conveyed before?

Julio Cortázar’s story has haunted me ever since I read it, returning more strongly at certain moments. One of those moments was in university when I learned about philosopher Thomas Nagel’s essay, “What Is It Like To Be a Bat?”, in which he argued that although we can learn the objective facts about something, even every detail about a bat’s echo-location sense, say, we cannot know what it is like for the bat to be a bat, or to echo-locate. Or even for another human to be their own self. You can get so far with knowledge, and with the imagination, but no further. You can know what it’s similar to, what is seems to be like—but not what it is actually like, the quality of it. There will always be something missing: subjectivity. If you experience it too, it’s not subjective, by definition. It’s this gap that we seem to overcome—but, I suppose, never truly overcome—when reading fiction.

Never stop trying, even so. If a human and an axolotl can do it, why not writers and readers? How did Pessoa put himself into so many characters, each with their own independent intellectual life (the poetic Dr. Reis, for example, was deeply affected by listening to a different heteronym, Alberto Caeiro, an uneducated shepherd and poet, reading his work)? In The Book of Disquiet, author Bernardo Soares observes a man named Fernardo Pessoa, and writes of him:

In his pale, uninteresting face there was a look of suffering that didn’t add any interest, and it was difficult to say just what kind of suffering this look suggested. It seemed to suggest various kinds: hardships, anxieties, and the suffering born of the indifference that comes from having already suffered a lot.

The thing is, Bernardo Soares, who is a book-keeper in a textile factory, doesn’t and didn’t exist. He was another heteronym (or, rather, just a semi-heteronym, less different from is author than a heteronym proper), of Pessoa, who, just to throw consciousness around a little more, signed his name (or orthonym) to the preface of Soares’ book, which was published half a century after the death of the nearly unknown preface-writer (I don’t know if we know when Soares died or whether it was at the same moment as his creator). This lifetime project and fragmentary masterpiece is now published as The Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa, and is considered one of the past century’s greatest works of literature3.

But as Adam Kirsch writes in this super article about the enigmatic, solitary Portuguese modernist,

The ultimate futility of all accomplishment, the fascination of loneliness, the way sorrow colors our perception of the world: Pessoa’s insight into his favorite themes was purchased at a high price, but he wouldn’t have had it any other way. “To find one’s personality by losing it—faith itself subscribes to that sense of destiny,” he wrote.

Kirsch adds that despite Pessoa’s name meaning person, there was “nothing he less wanted to be.”

Perhaps he’d have rather not be an axolotl, though.

Wishing you a good week, friends. May you transfer your consciousness into many other bodies—but not an axolotl’s, because as Cortázar warns us, “every axolotl thinks like a man inside his rosy stone semblance”, and you might get stuck.

—Carlyn

Italian novelist and Lusophile (lover of all things Portugal and Portuguese) Antonio Tabucchi, or his protagonist, also encounters the deceased Pessoa in the short, atmospheric novel Requiem: A Hallucination, which I have read and heartily recommend.

First-person narration is not the only way to do this! Please remind me if I forget to get to it in the coming weeks—second person is not my favourite thing but it offers a very enjoyable way of being immersed in an experience. And there’s nothing wrong with good old observation and empathy via third-person narration, either.

Just scroll through some of these quotations from it in English translation and you get a sense of why.