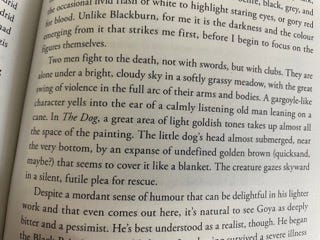

The title of this post is from a Gauguin painting often used to illustrate fundamental questions about philosophy or about the origins of humanity. I think it might be a good title for a little series, so I’m optimistically calling this #1.

Don’t get your hopes up though (if a series in an email newsletter is a thing that gives you hope). Because what I wanted to talk about is this: I find that I lack continuity. Every morning when I wake up, it is as if I am a new person. Not new as in fresh and dewy, just new as in discontinuous. As if I had died overnight. It seems always possible that the traces of incoherent dreams clinging to the walls of my brain are actually the memories of an entirely different life, perhaps my real life. It’s not like Memento, where it’s discontinuous and I’ve forgotten things. Just discontinuous.

As a chronic pain-causing condition makes sleep difficult for me, I’ve trained myself, with the help of an obliging, early-breakfasting cat (she chews on cables to haul me out of bed, an infallible alarm clock) to wake up extremely early, before my sore spine can do it for me. Then I return to bed, fortified with pain medication, for a much better sleep for a few hours before it’s time to get up. While my resulting sleep schedule is insane (though far better than the previous one of writhing around in pain over endless white nights), it does have the advantage of me being awake at regular intervals, like a medieval, or up to roughly the 17th century, biphasic sleeper, with their first sleep and their second sleep and “the watch”—a period during which you might pee on the fire, murder someone, have sex, brew some beer, check on the sheep, or feed the cat.

This reduces the feeling of discontinuity a bit, as I seem to be awake and in this life most of the time. Still, that nagging feeling continues. It seems quite possible that my consciousness, which is here now as I write, is somewhere else when I’m not aware of it, latching onto some other biographical facts for its reality, just as it does when reading a novel.

The memory of a memory of drowning (Lloyd Alexander’s Westmark), a talking gargoyle (Lynne Reid Banks’ The Farthest Away Mountain), a smelly human trapped in a smelly cage, kept like a monkey by alien scientists (Monica Hughes’ Space Trap): these and so many other tiny, haunting details of half-remembered novels I read as a child now have exactly the feel of memories: inarticulate1, sensory, immersive, and entirely subjective because seen from inside, from that consciousness that it is so hard, or impossible, for us to imagine simply dissolving into nothingness with the death of the body.2 Novels read later, if they trigger your deepest, inchoate feelings, may have a similar effect. Events or images that are slightly horrible, or alien, idiosyncratic, irreplicable, the opposite of formulaic or cliched, beautiful but strange—such things that throw you off just slightly, giving you the feeling that you, too, have woken up from, possibly, an entire other life, can do it.

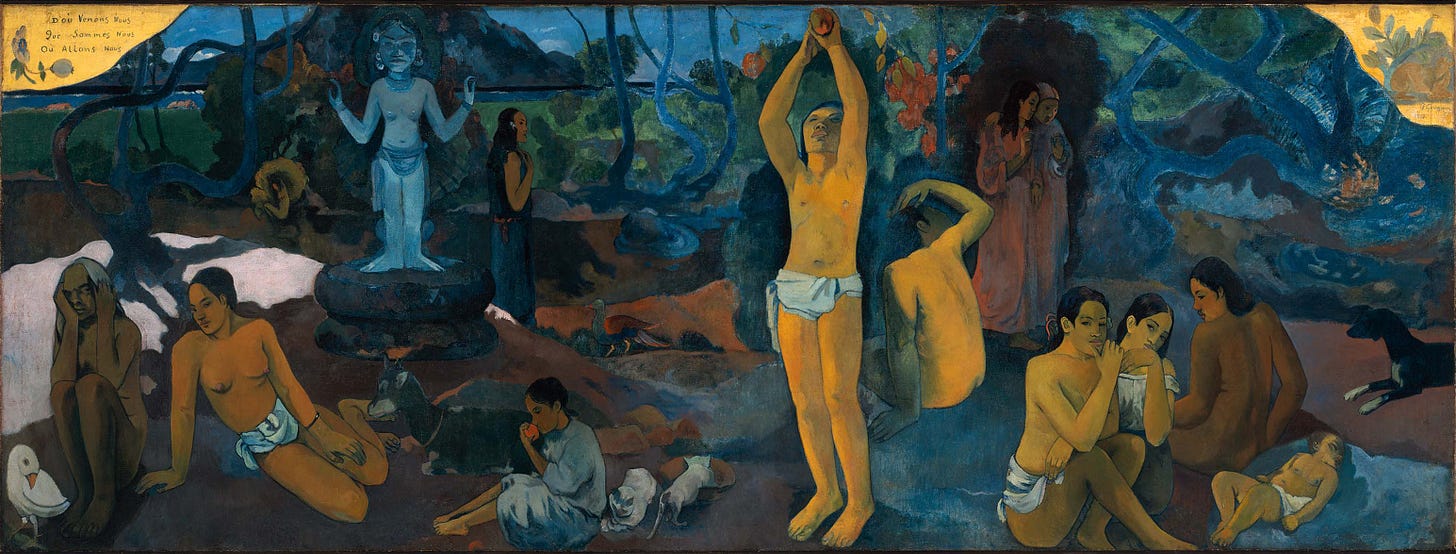

I keep forgetting the origins of, and then finding again (this happened just now) a passage from a book, that turns out to be Uruguayan writer Mario Benedetti’s The Truce, in which the narrator describes how his grandmother dealt with his reluctance, as a child of four years old or even younger, to eat. Putting on his uncle’s oversized raincoat and dark glasses, the grandmother, face hidden by glasses and hood, would go outside and rap at the window. The boy’s mother, a servant, an aunt—whichever accomplice was around—would then shout “It’s Don Policarpo!” (Old Mr. Policarpo). Don Policarpo was, the little boy was told, a sort of monster who punished children who didn’t eat. The child was, of course, frightened every time and immediately swallowed whatever unappetizing porridge was in front of him. It became a cruel family joke for a time to torment the child in this way, though the adults didn’t realize how truly terrified he was. Don Policarpo then haunted him, for years, in nightmares—a line of Policarpos standing silently, shrouded in mist, their backs turned to him. Over time, the narrator tells us, the feeling associated with ‘his’ Policarpos, the unrelieved waiting for the silent figures to turn around, shifted from horror to fascination, and sometimes, during a different dream, he would realize that he’d prefer to be dreaming about his Policarpos.

As if it were my own childhood nightmare, the image of a line of dark, rubbery, raincoated figures all called Policarpo has slipped in and out of my memory since I read this maybe a decade ago—a Spanish-language writer, someone named Policarpo, the raincoats, the silence, the feeling of anticipation—over and over I’ve tracked it down with a bizarre series of keywords in Google, rejecting the first hit, a children’s story about a kid named Policarpo who meets the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda (by practically novelistic chance, the subject of Friday’s newsletter).

It seems possible that when my consciousness goes to sleep, it wakes up in the dream of a child faced with a row of silent Policarpos.

Alberto Manguel’s superb, neglected novella, Stevenson Under the Palm Trees, haunts me, particularly with one shocking scene involving a fire that takes place in a saloon:

At last the doors were broken. There was a burst of flames as the night air fed the fire, and then, for a long moment, a hideous and eerie silence. Wrapping themselves in pieces of wet cloth, five or six men braved the furnace. A moment later, Stevenson saw them carry out a vaguely human form, black as coal. A loud wail rose from the crowd. Two, three more bodies were hauled out. Then, with a sickening snap, the beams of the roof caved in, trapping one of the rescuers. The chief justice was bellowing out orders, seemingly to no one in particular. A child began to cry.

Upon retrieving the book (I’d loaned it out), and searching for this remembered passage, I quickly reread the extremely short book and found that the resonant horror of this scene is disturbing not only because of its cadence and selective, sparingly described details of horror, but actually it is one culminating point of the sense of fragmented consciousness, with its hallucinatory uncertainty and fevered nights and nightmare logic, that infuses the entire book. Drawing on our own sense of unstable reality and unstable personality, in this story spun from the last days of Robert Louis Stevenson, the author of Treasure Island, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Black Arrow, and Kidnapped, among other great novels of adventure and horror, Manguel reaches into each reader’s personal store of nightmares. I have been scheming an essay about Stevenson himself, and about the literature of adventure, so I won’t go further now to describe how Stevenson also creates the sense of being haunted by literature, for example with the unforgettable character of Long John Silver in Treasure Island.

Julio Cortázar’s short story, Axolotl (which I’ll have to write a whole essay about at some point), haunts me in this way. Almost any good bits that I quote will give it away, so I’ll be careful:

Then my face drew back and I understood.

Please track down this story—it’s part of Cortázar’s collection Blow-Up and Other Stories (originally published as End of the Game and Other Stories)—so that we can talk about it in a few weeks.

The same discontinuity I feel in life and find reflected in fiction, I feel in novels as well—I struggle to perceive or remember plots as a whole (even though I need them in some way, as essential scaffolding without which there is no forward motor driving me from room to room of the story’s expanding but finite house). But these haunting, individual impressions, tiny units of feeling or perception, can be indelible. This quality of fiction—to give you experiences that are so vague and formless that they are just like our real, earliest, wordless experiences, as formative and indescribable or barely describable as they are—seems completely magical to me. What am I doing here? I ask myself this morning as I sit down to write by hand at the kitchen table, having resolved to tear myself away from the screen once in a while. Making magic. Trying to, anyway.

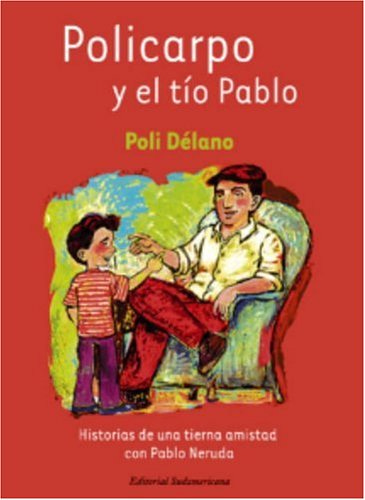

Ekphrastic writing is writing that evokes a piece of art with words. It’s a genre I love, and that I slid in among the many different genres in my book, On Opium. Part of the reason I like it is that it allows for the summoning up of the visual quality of haunting, with words. For example, I wrote about the painting above just as, in fiction, I might select details that will most powerfully evoke the disturbing image for my reader, and fix it in their mind when other aspects of the book have fallen away. Here’s the image, which the reader doesn’t get to see.

Here’s the short description designed to re-emerge in readers’ dreams.

This raises a question, though. Why would anyone in their right mind want to “live more lives” by inviting imaginary characters and imagery to distress, disturb and haunt them?3

I don’t have an answer for that. Truly, I don’t know.

Wishing you all a week in which your dreams are sweet, your days are light—and your reading is troubling, memorable, and strange.

-Carlyn

In fact, some adult research was required to put words and context to my memories, which strips them of their full, original subjectivity and immediacy.

Intellectually, I believe that consciousness is an emergent property of the material reality of our brains that will turn off when I do, but viscerally and emotionally, I can only imagine that when I die my consciousness will emerge, in someone else’s brain, just as every night my awareness goes to sleep, only to flick on with the morning alarm, restored to my own brain after perhaps gallivanting into someone else’s, someone wakeful, not yet on their first or second sleep, during nighttime dreams. Such are the limitations of the brain trying to understand itself.

If this seems highly unappetizing, perhaps my project is not for you. Return to your bucket list with a clean if boring conscience. If it appeals, though, welcome and please stay for the haunting.