Dear Gentle Readers,

it’s a truism that bad guys are the best parts to play, that villains have the most fun, that heroes are lantern-jawed and boring while baddies are simply delightful.

Here I think of an old Muppet Show episode where Vincent Price, playing himself—Vincent Price-who-is-also-a-great-cook—is a distinguished member on a discussion panel about food. The renowned actor/villain/scene-chewer, unleashes his inner villain as he munches on Kermit the Frog’s leg after a fellow panelist on the frog’s talk show (a monster, of course) starts eating his other co-panelists. With his famously, deliciously evil grin, Price says “Froggie, you have to admit, you DO look tasty.”

The dastardly delivery is delicious.

As an audience member—or as a reader—we savour, in that luscious, sensory way, the badness of a good baddie. An appealing villain is one who really enjoys their villainy, who hams it up at least a little, who’s colder than ice or fiery as hell. For the purposes of a good book, even those villains who really disturb and distress us—in those novels in which Vincent Price-y melodrama and enjoyment are not the literary objectives—it’s still often wise for an author to give the villain something that makes us feel, even secretly or subconsciously, a little envious—if only of their freedom to not feel guilt at the terrible things they do, because we’d like to not feel guilt about our own relatively insignificant moral transgressions, and so we get a giddy vicarious pleasure at their excessive freedom from qualms.

Certainly he took no pains to hide his thoughts, and certainly I read them like print. In the immediate nearness of the gold, all else had been forgotten: his promise and the doctor’s warning were both things of the past, and I could not doubt that he hoped to seize upon the treasure, find and board the Hispaniola under cover of night, cut every honest throat about that island, and sail away as he had at first intended, laden with crimes and riches.

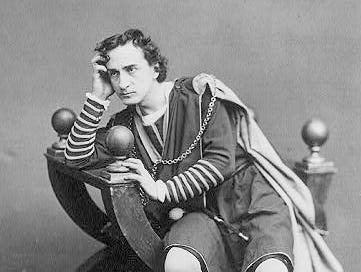

So writes Jim Hawkins of the treacherous sea cook, Long John Silver, in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (to which I dedicated a good bit of this previous Live More Lives, about adventure). It’s not only the overt wickedness of the man that makes him such an appealing villain, but his easily-observable good points, too—physical courage, demonstrated on various occasions; great cleverness and ability to see which way the wind is blowing and use this knowledge to his advantage; and the moments of good will he displays towards young Jim, as here:

I like that boy, now; I never seen a better boy than that. He's more a man than any pair of rats of you in this here house, and what I say is this: let me see him that'll lay a hand on him--that's what I say, and you may lay to it.

And most of all, there is the confusing part of his personality, the ambiguous part, which comes out in his shifts from friend to foe, or in his display of a creepy sort of humility as he begs friendship that, even when betrayed, always seems to have some kernel of authenticity inside it, as when he tells Jim that “you and me must stick close, back to back like, and we’ll save our necks in spite o’ fate and fortune.”

Of course, the moment we are moved to a grudging sympathy for this attractive, ruthless character, he runs off with the treasure. And it’s satisfying that he never gets his comeuppance in the end.

That’s not to say that it’s only the defiant and gleeful tramplers of our most cherished moral lines who make memorable villains. The haunted and pitiful and repressed can be memorable characters as well. Raskolnikov in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, which perhaps the first complex psychological portrait of a murderer in fiction (setting aside Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex and a number of other early contenders), commits a murder for what seems a trivial reason—he tries to justify it as the result of his embrace of nihilism. At first Raskolnikov, an impoverished ex-law student, seems reminiscent of the real-life wealthy, apparently conscienceless students Leopold and Loeb, and familiar to modern-day readers through the over-used ‘psychopath’ stereotype—but then he spends the rest of the book haunted by guilt.

The senseless murder committed by Meursault in Albert Camus’ The Stranger seems to be not truly emotionless, despite appearances, but to lack psychological insight or to suffer from psychological repression and philosophical confusion, the subtle exploration of which again constitute most of the rest of the book.

Still, our interest here isn’t simply in observing the villain, nor in the empathy that, we are frequently told in sciencey-sounding and suspect terms, reading actually programs into our brain boxes, and which might allow us to appreciate the humanity and pain within the psyche of others1, including the most atrocious of historical or imaginary humans. Here at Live More Lives, we crave experience, and the otherwise unattainable experiences that literature—and most particularly, the novel—provide.

So let’s look at how we experience villainy from the perspective of the villain.

Humbert Humbert, the first-person protagonist of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, which begins with the famous words, “Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins,” and then continues, stylishly, into a full confession of at least two, perhaps three crimes:

My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta. She was Lo, plain Lo, in the morning, standing four feet ten in one sock. She was Lola in slacks. She was Dolly at school. She was Dolores on the dotted line. But in my arms she was always Lolita. Did she have a precursor? She did, indeed she did. In point of fact, there might have been no Lolita at all had I not loved, one summer, an initial girl-child. In a princedom by the sea. Oh when? About as many years before Lolita was born as my age was that summer. You can always count on a murderer for a fancy prose style. Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, exhibit number one is what the seraphs, the misinformed, simple, noble-winged seraphs, envied. Look at this tangle of thorns.

It takes a while for the reader (at least, a reader not already conditioned by the book’s fame to condemn this appealing monster despite his literary tricks) to understand which side we are on, or should be on, and to appreciate the genuine monstrousness of his crime—not the murder, which is far less significant in the novel, but the permanent destruction of Dolly’s childhood. Because he shows such brio in his writing style—Nabokov’s, which is the suave and ‘European’ Humbert’s—we are seduced even more thoroughly than we would be anyway by our perspective, trapped as we are in the first person, held within his confessing-and-justifying consciousness.

And in fact, the simple enjoyment we take from the best parts of the book is the point: it can be very nice being the villain. We are swept along for a shamefully long time by the exuberance of Humbert’s sneaky justifications.

Freddie Montgomery, John Banville’s probably psychopathic first-person narrator in The Book of Evidence, tells us,

By the way, leafing through my dictionary I am struck by the poverty of language when it comes to naming or describing badness. Evil, wickedness, mischief, these words imply an agency, the conscious or at least active doing of wrong. They do not signify the bad in its inert, neutral, self-sustaining state. Then there are the adjectives: dreadful, heinous, execrable, vile, and so on. They are not so much as descriptive as judgmental. They carry a weight of censure mingled with fear. Is this not a queer state of affairs? It makes me wonder. I ask myself if perhaps the thing itself - badness - does not exist at all, if these strangely vague and imprecise words are only a kind of ruse, a kind of elaborate cover for the fact that nothing is there. Or perhaps words are an attempt to make it be there? Or, again, perhaps there is something, but the words invented it. Such considerations make me feel dizzy, as if a hole had opened briefly in the world.

Montgomery, as preternaturally good with words as his creator (Banville’s command of the English language existing in a sort of different dimension from most other writers’2), reveals his murderously mirror-like nature when tells us that the only way another creature can be known is ‘on the surface’. That, he tells us, is “where there is depth”. And when he claims to be

just amusing myself, musing, losing myself in a welter of words. For words in here are a form of luxury, of sensuousness, they are all we have been allowed to keep of the rich, wasteful world from which we are shut away.

Upon capture, he imagines speaking up in court to tell the story of how,

I am kept locked up here like some exotic animal, last survivor of a species they had thought extinct. They should let in people to view me, the girl-eater, svelte and dangerous, padding to and fro in my cage, my terrible green glance flickering past the bars, give them something to dream about, tucked up cosy in their beds of a night. After my capture they clawed at each other to get a look at me. They would have paid money for the privilege, I believe. They shouted abuse, and shook their fists at me, showing their teeth. It was unreal, somehow, frightening yet comic, the sight of them there, milling on the pavement like film extras, young men in cheap raincoats, and women with shopping bags, and one or two silent, grizzled characters who just stood, fixed on me hungrily, haggard with envy. Then a guard threw a blanket over my head and bundled me into a squad car. I laughed. There was something irresistibly funny in the way reality, banal as ever, was fulfilling my worst fantasies.

Short story writer and novelist Angela Carter takes on many bad guys, famous in literature or real life, and invented whole cloth. Sometimes she redeems them. But sometimes, she simply brings us inside, as for example (though mysteriously without using the first person) on the steamy hot day of the 4th of August, 1892, in Fall River, Massachusetts, when

after breakfast and the performance of a few household duties, Lizzie Borden will murder her parents, she will, on rising, don a simple cotton frock—but under that, went a long, starched cotton petticoat; another short, starched cotton petticoat; long drawers; woollen stockings; a chemise; and a whalebone corset that took her viscera in a stern hand and squeezed them very tightly. She also strapped a heavy linen napkin between her legs because she was menstruating.

In this short story from Carter’s collection Black Venus, we learn, from the narrator, that Lizzie Borden is the beloved younger daughter of a widowed miser who has remarried, to a woman she hates. At 32, Lizzie is unmarried and lives at home like a child, stifled by her life. We see her from outside her consciousness. The narrator doesn’t hold back the revelation of who the protagonist is like a jump scare: instead, she reminds us of the old rhyme about the axe and the forty whacks. She tells us what Lizzie looks like in photographs taken before she becomes famous (she has the jaw of a concentration-camp attendant and the mad eyes of the New England saints, the eyes of a person who does not listen to you—though in later photos, from her old age, the mad light has gone out and she wears a pince-nez). The narrator comments on what will happen before, fatefully, it does.

But also, though still in third-person, we move closer. The following quote begins in third-person, no longer omniscient but from the tone perhaps adopting the voice of someone in the community. It ends in close third-person (although the narrator retains the omniscience to tell us what her father feels, too), and this takes us deeper into Lizzie’s psyche and motivations:

She doesn’t weep, this one, it isn’t in her nature, she is still waters, but, when moved, she changes colour, her face flushes, it goes dark, angry, mottled red. The old man loves his daughter this side of idolatry and pays for everything she wants, but all the same he killed her pigeons when his wife wanted to gobble them up.

That is how she sees it. That is how she understands it. She cannot bear to watch her stepmother eat, now. Each bite the woman takes seems to go: ‘Vroo croo.’

Does this give us empathy? A sort of understanding, maybe. This story of Lizzie Borden (who was ultimately acquitted but popularly believed to be guilty of the double murder) doesn’t, though—at least not to me—give me that delicious (the best villains are described in gluttonous, appetitive terms, like habit-forming substances or ‘sinful’ desserts) sense of boundaries gleefully violated, of the freedom of it, any more than guilty, haunted Raskolnikov does. The story is enjoyable but the character lacks the bravado that makes the reading of Long John Silver or even Humbert Humbert a pleasure, if, on moral reconsideration, a guilty one.

Licentiousness and transgression, though, aren’t the only experiences we may enjoy by means of villainous characters, though. In an afterword to The Bloody Chamber, another of her marvellously macabre story collections, Carter writes,

The Gothic tradition in which [Edgar Allan Poe] writes grandly ignores the value systems of our institutions; it deals entirely with the profane. Its great themes are incest and cannibalism. Character and events are exaggerated beyond reality, to become symbols, ideas, passions. Its style will tend to be ornate, unnatural—and thus operate against the perennial human desire to believe the word as fact. It’s only humor is black humor. It retains a singular moral function—that of provoking unease.

And unease, as we have discussed before, is indeed one of the great experiences fiction has to offer. Perhaps this is why not everyone likes what I’d call good novels. But as we all know, they’re missing out.

May your regular experience be easy and your literary experience interestingly uneasy or excitingly transgressive this week.

See you Sunday, dear Gentle Readers.

-Carlyn

ps please note that this essay has been edited since first publication to finesse various details.

INTERVIEWER

Do you really hate your own novels?

BANVILLE

Yes! I hate them. I mean that. Nobody believes me, but it’s true. They’re an embarrassment and a deep source of shame. They’re better than everybody else’s, of course, but not good enough for me. There is a great deal more pain than pleasure in writing fiction. It’s only now and then, maybe once every three or four days, that I manage to write a sentence in which I hear that wonderful harmonic chime that you get when, say, you flick the edge of a wine glass with a fingernail. That’s what keeps me going. [from the Paris Review’s interview with the self-described graphomaniac novelist]